FlareOn 2019 Writeup - Part 2

01 Nov 2019Part 2 contains my solutions for challenges 4 and 5.

Table of Contents

Challenge 4 - dnschess

Challenge 5 - demo

References

I moved this article to my new blog. Click here to read it there.

Challenge 4 - Dnschess

Task:

Some suspicious network traffic led us to this unauthorized chess

program running on an Ubuntu desktop. This appears to be the work

of cyberspace computer hackers. You'll need to make the right moves

to solve this one. Good luck!

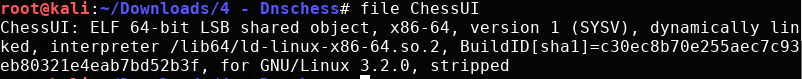

This time we’re dealing with a 64bit ELF binary.

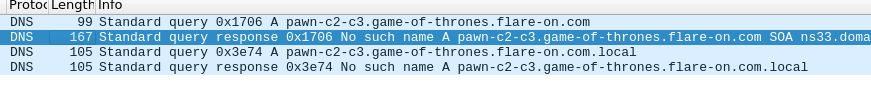

One of the files in this challenge is a packet capture containing some DNS traffic.

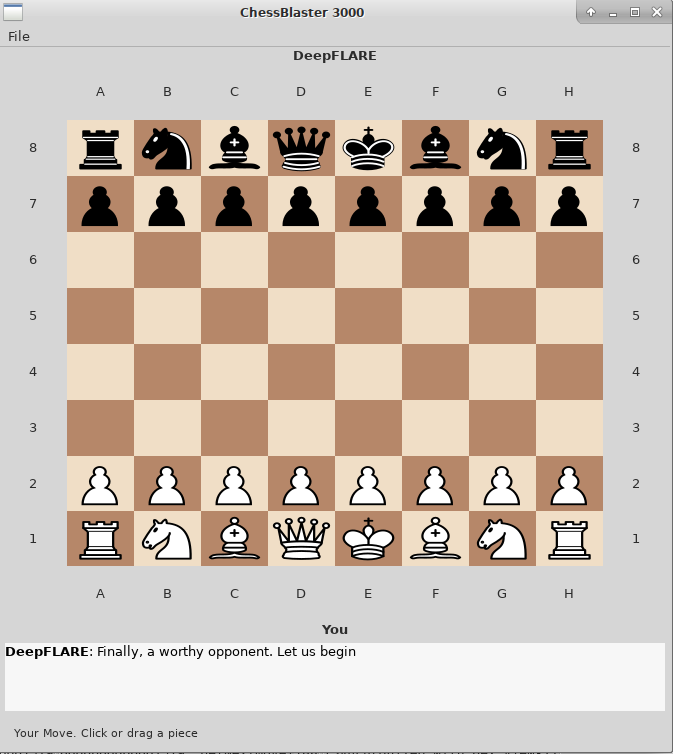

When executed a GUI chess board is displayed.

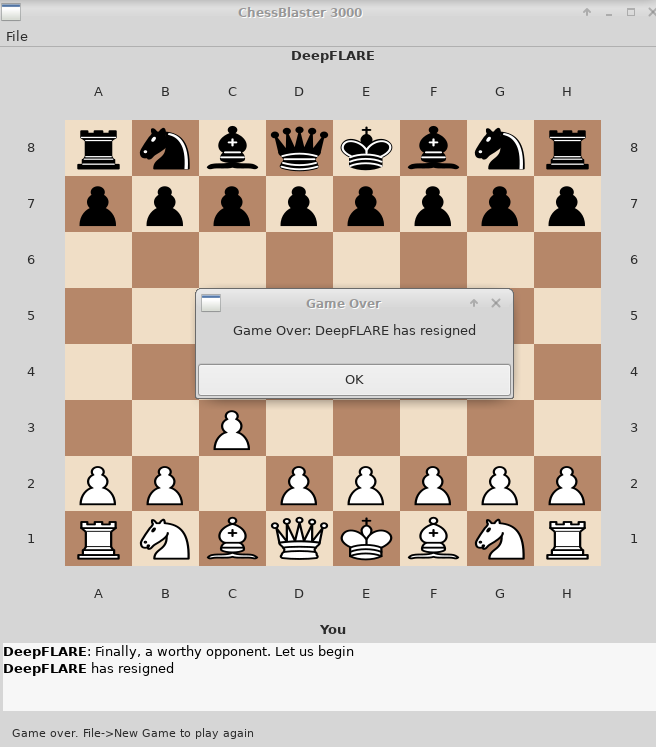

If I try to play a move I get a message that DeepFLARE has resigned and the game is over.

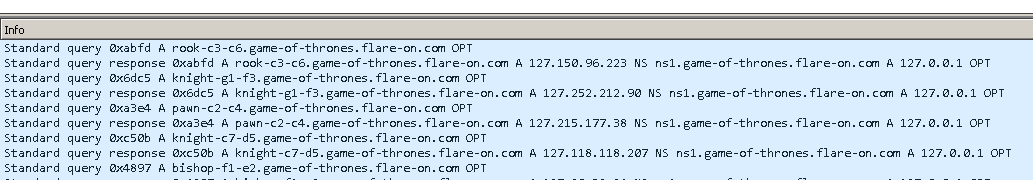

I captured the network traffic while running the program to see what network connections it tries to make.

After I made a move a DNS request was made for a domain in the following format

piece-source-destination.game-of-thrones.flare-on.com.

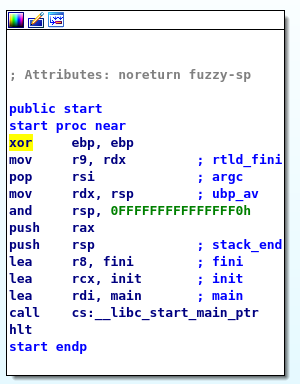

Now to disassemble it! The first step is to identify the main function inside the entry point. Main is the argument (pointer) passed in the rdi register to the libc_start_main_ptr function.

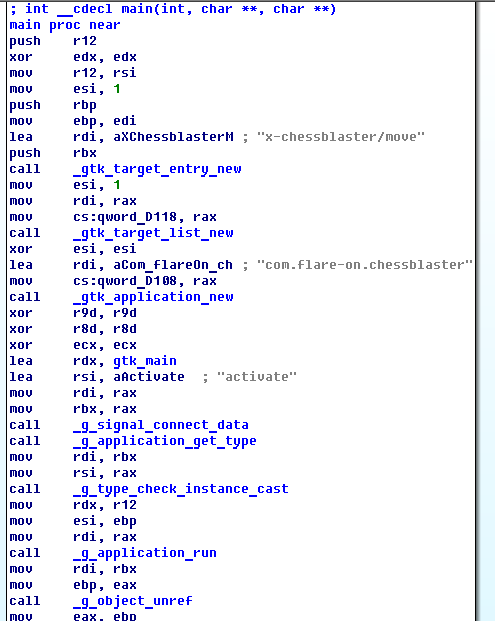

Because the application uses GTK, inside the main function there are some GTK related functions. I never used GTK, but after a bit of googling[1] I managed to identify the function which GTK calls when the application starts. I named it gtk_main.

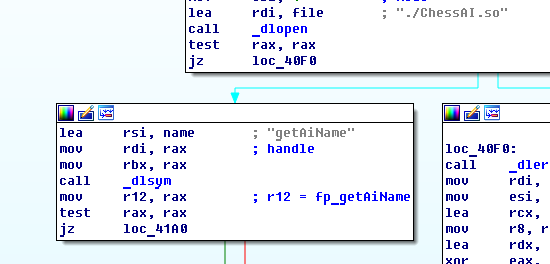

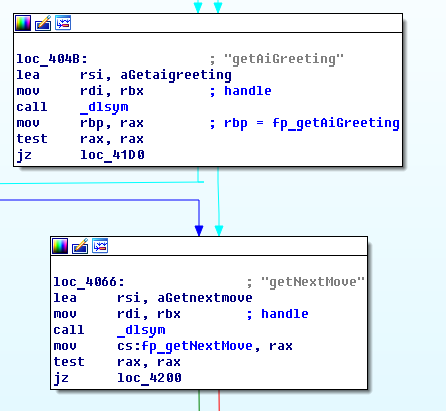

Near the end of gtk_main, the application loads the ChessAI.so library and then finds the address of getAiName function.

Then it also finds the addresses of getAiGreeting and getNextMove functions.

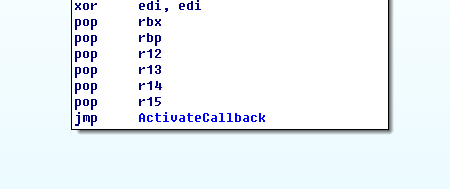

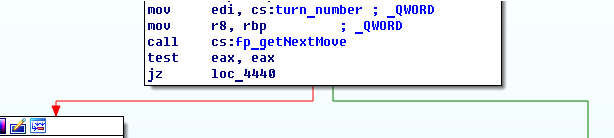

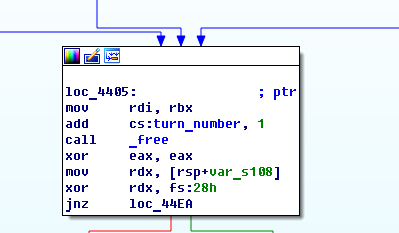

At the end of gtk_main the program jumps to a function I called ActivateCallback. Inside this function the global variable which counts the turn number is initialized to 0. I didn’t make detailed notes, so I don’t remember how I figured out the meaning of this variable.

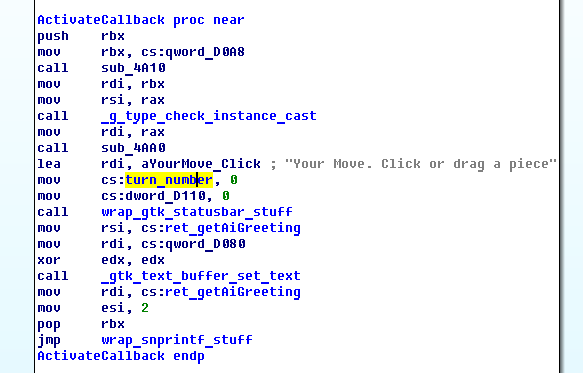

Checking the xrefrences for the getNextMove function pointer leads to the function responsible for calling it. You can see that the turn number is passed in the edi register as an argument.

At the end of the function the trun counter is increased by 1.

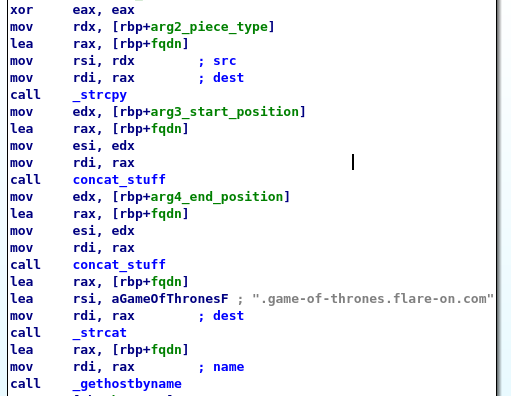

Now it’s time to analyze the ChessAI.so library and see what getNextMove actually does. At the beginning it concatenates strings in order to construct a FQDN and then calls gethostbyname to try and resolve this FQDN to an IP address.

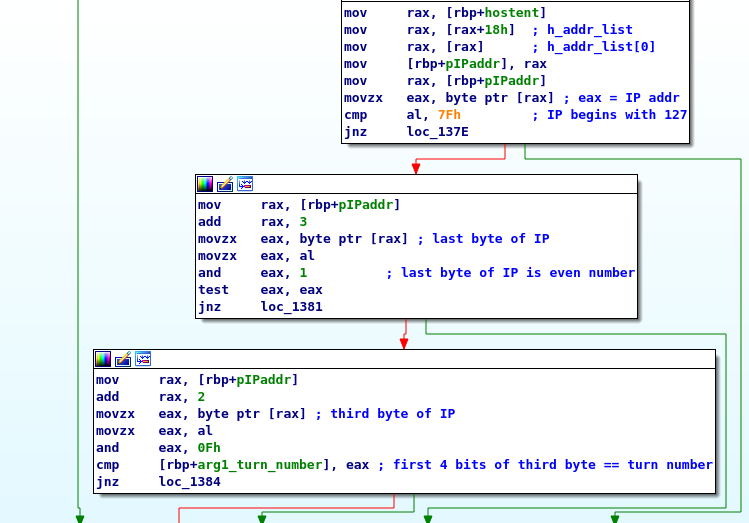

If it gets an answer the following checks are performed:

- Checks if the first byte of the IP address is equal to 127. This means that the IP address should be a loopback address.

- The last byte of the IP address must be an even number.

- The first 4 bits of the third byte must be equal to the current turn number. This means that the maximum number of turns is 16 (4 bit values range from 0 to 15).

After these checks a long block of assembly instructions follow which I won’t show here, because it’ll take too much time. This block is responsible for decryption of the flag, which is stored as a global array. The second byte of the IP address is used as a key to decrypt the array containing the flag. Decryption is done by XORing this byte with the 2*n and 2*n+1 elements from the array with the encrypted flag, where n is the current turn count.

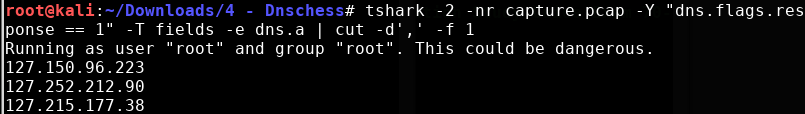

The list of IP addresses can be exctracted from the provided pcap file with the following command:

tshark -2 -nr capture.pcap -Y "dns.flags.response == 1" -T fields -e dns.a | cut -d',' -f 1 > ip_addresses.txt

I wrote a python script to check which IP addresses will satisfy the necessary conditions, order them by the their respective turn number (the first 4 bits in the third byted) and generate the decryption key.

f = open("ip_addresses.txt","r")

addresses = f.read()

f.close()

addr = addresses.split('\n')

keys = {}

for ip in addr:

bytes = ip.split('.')

if len(bytes) != 4: break

for i in xrange(16):

if int(bytes[3])%2 == 0 and (int(bytes[2])&0x0f == i):

# unordered

keys[i] = int(bytes[1])

k = []

# sorted

for i in xrange(len(keys.keys())):

k.append(keys[i])

print k

It produces the following output:

[53, 215, 159, 182, 252, 217, 89, 230, 108, 34, 25, 49, 200, 99, 141]

I wrote a second script to decrypt the flag:

encrypted_flag = bytearray([0x79,0x5a,0xb8,0xbc,0xec,0xd3,0xdf,0xdd,0x99,0xa5,0xb6,0xac,0x15,0x36,0x85,0x8d,0x09,0x08,0x77,0x52,0x4d,0x71,0x54,0x7d,0xa7,0xa7,0x08,0x16,0xfd,0xd7])

key = [53,215,159,182,252,217,89,230,108,34,25,49,200,99,141]

s = ''

for i in xrange(len(key)):

s+= chr(encrypted_flag[2*i] ^ key[i])

s+= chr(encrypted_flag[2*i+1] ^ key[i])

print s

And the flag is:

LooksLikeYouLockedUpTheLookupZ

Challenge 5 - demo

Task:

Someone on the Flare team tried to impress us with their demoscene skills.

It seems blank. See if you can figure it out or maybe we will have to fire them.

No pressure.

When executed a window appears with an animation of rotating 3D object.

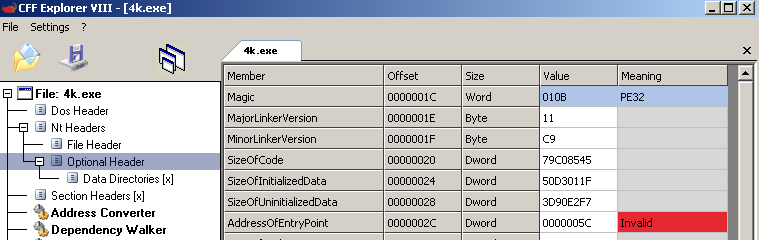

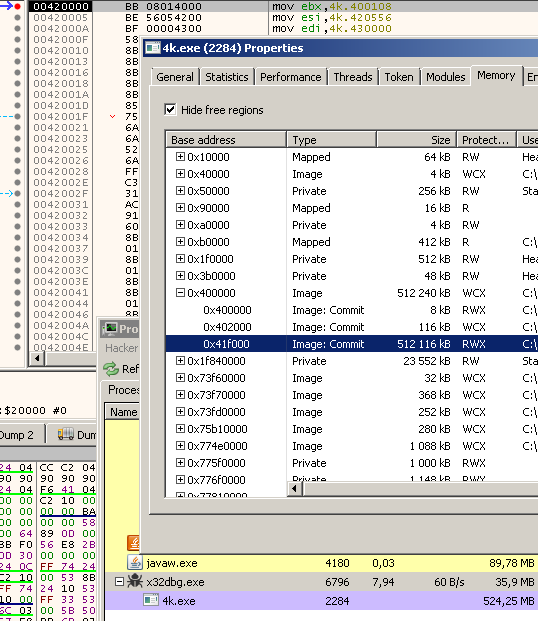

In CFF Explorer you can immediately notice a weird looking address of entry point (0x5c):

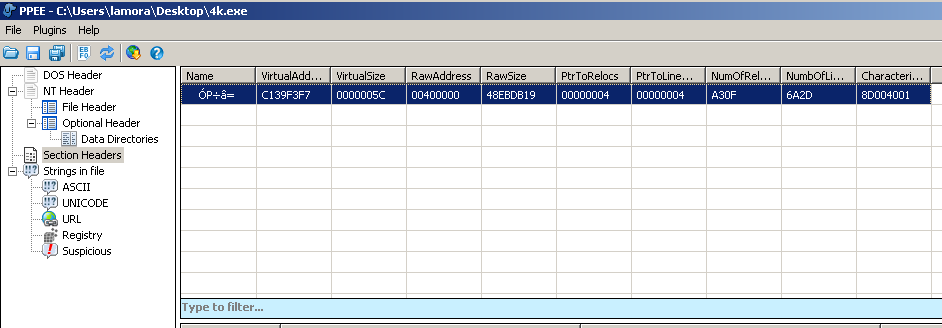

CFF Explorer didn’t show any sections, so I tried opening the file in PPEE, which displayed one unusual looking section:

It looks that it might be packed, but to confirm I opened it in Detect It Easy and sure enough the entropy of the file is high, which indicates it could be packed.

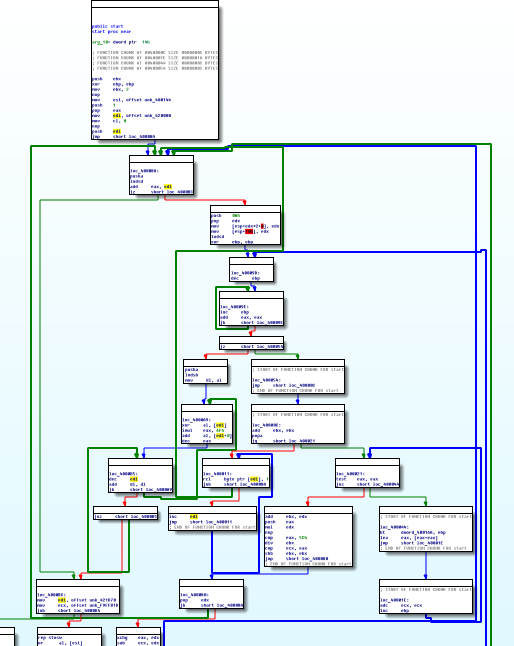

The disassembly of the unpacking procedure looked complex and it would’ve taken me too much time to reverse it.

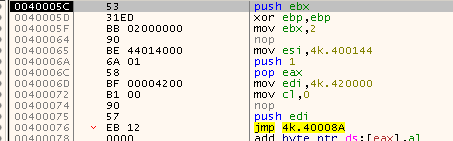

Instead of trying to reverse the unpacking procedure, I tried the usual trick with dumping the unpacked code. In the beginning of the code you can see that it uses the address 0x420000.

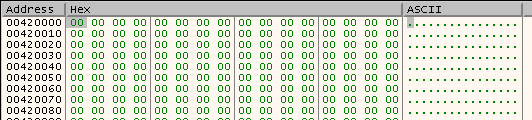

If you go to this address in memory you’ll notice that it’s empty and filled with null bytes. Maybe that’s where the unpacked code is going to be stored?

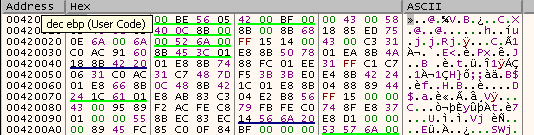

Continuing the execution of the program shows that this memory is indeed filled with some data.

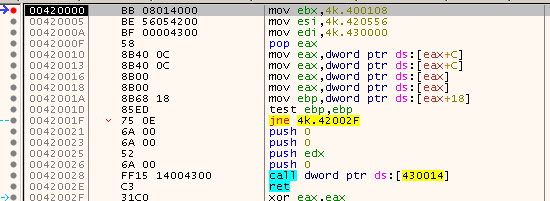

I placed a memory execution break point on address 0x420000 and when I ran the program again, the break point was hit. So this is where the unpacked code is stored.

The next step was to dump the unpacked code. While the code was paused at the break point at 0x420000, I used Process Hacker to dump the whole memory region which was allocated for the code. The dump was 500MB, but most of it was just null bytes, which is why I used hex editor to remove the unnecessary bytes and leave only the executable code. The final binary was 12KB.

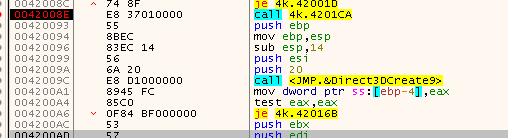

At the beginning the unpacked code locates the address of kernel32.dll, then finds the address of LoadLibraryA function in order to load additional libraries and import additional functions. Some of the libraries it tries to load are d3d9.dll and d3dx9_43.dll which are DirectX 9.0 libraries. When the importing of libraries and functions is finished, x64dbg resolves some addresses to function names. Some of them were DirectX functions, which means it probably uses DirectX to render the rotating 3D object.

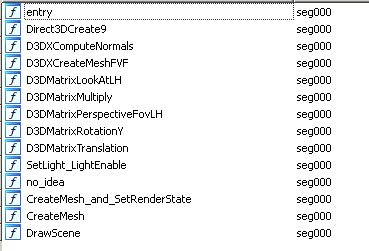

I used the resolved function names from x64dbg to locate and rename the functions in IDA.

I wasn’t familiar with DirectX, so before continuing with the analysis I had to do some reading[2]. The second reference at the end of this post contains everythig you need to know to solve the challenge. Read everything up to page 33. I’ll try to summarize some of the information.

- 3D objects are represented by a mesh of triangles which approximate the shape of the object.

- The point where two edges of a triangle meet is called a vertex.

- Triangles are described as an array of three vertices.

- Meshes are described as an array of triangles.

- A scene is a collection of objects (meshes).

- The object’s triangle list is defined in a local coordinate system.

- To bring together multiple objects in a scene, their coordinate system has to be transformed to that of the scene (a global coordinate system). This transformation sets the relationship of the objects to each other in position, size and orientation. This is done with the IDirect3DDevice9::SetTransform method.

- The camera is transformed (placed) at the center of the world coordinate system and rotated to face the positive Z axis. All geometry in the world is transformed (rotated) along with the camera (facing the Z axis) so that the view of the world remains the same. This transformation is called the view space transformation and is computed with the D3DXMatrixLookAtLH method and then it can be set by the IDirect3DDevice9::SetTransform method.

- All drawing methods must be called inside an IDirect3DDevice9::BeginScene and IDirect3DDevice9::EndScene method pair.

- Drawing can be done with the DrawSubset method.

After importing the necessary functions and libraries the unpacked code initializes DirectX and the window where the drawing is going to be done. At the end of the code it calls some functions responsible for creating 3D objects (meshes) and then drawing them on the window.

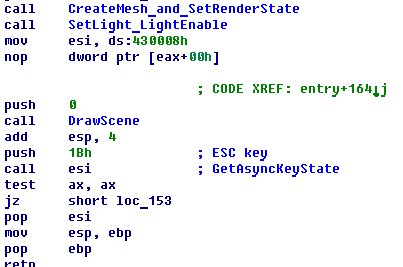

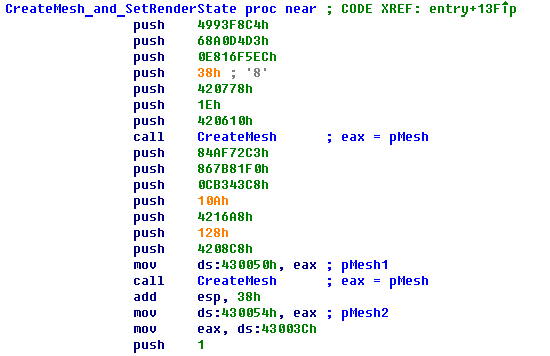

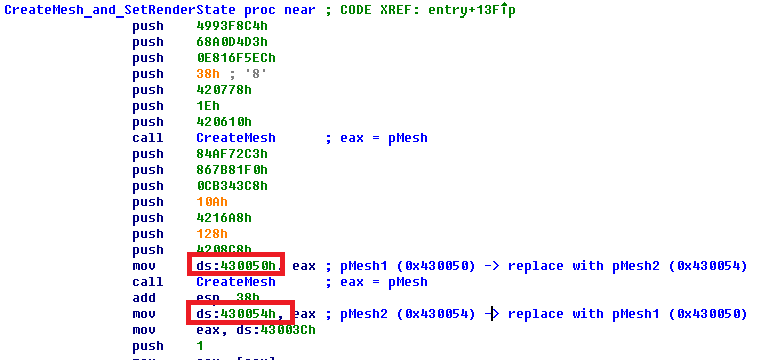

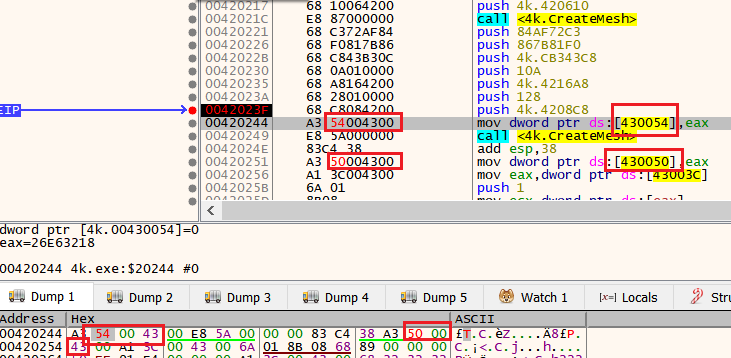

The first function CreateMesh_and_SetRenderState creates two meshes. The pointers to these meshes are stored at addresses 0x430050 and 0x430054. This is strange because when I ran the program there was only one object visible.

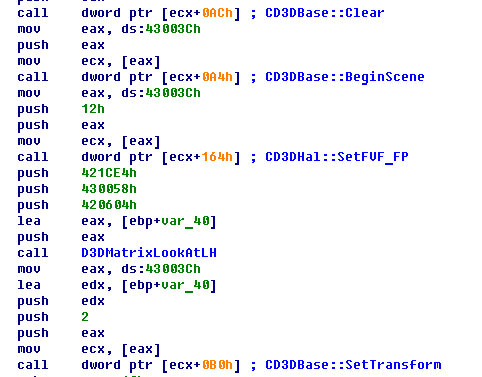

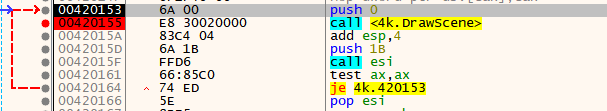

The DrawScene function begins as expected. It starts with BeginScene method and then sets the view space transformation of the camera.

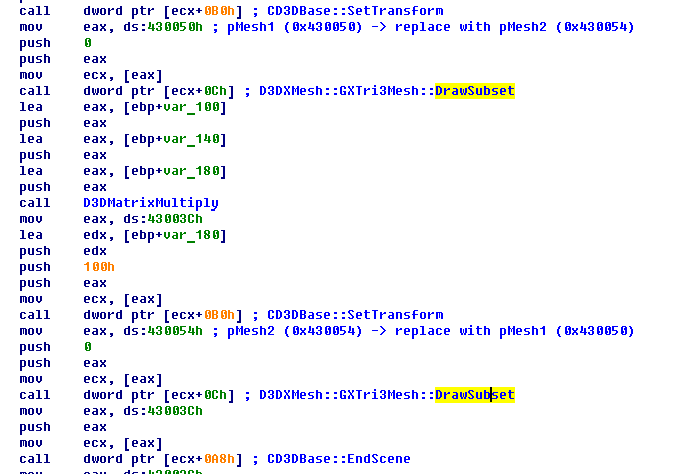

Later in this function you can see two DrawSubset methods, which draw the two 3D objects (meshes). The camera placement wasn’t changed, this means that only one object is in the field of view of the camera. Maybe the other object is the flag?

If the addresses where the pointers to the objects are saved get swapped, then the second object will be drawn in the field of view of the camera!

I swapped the pointers by patching the code in memory with a debugger.

Then I placed a break point at the DrawScene function so I can easily pause the execution at the first frame.

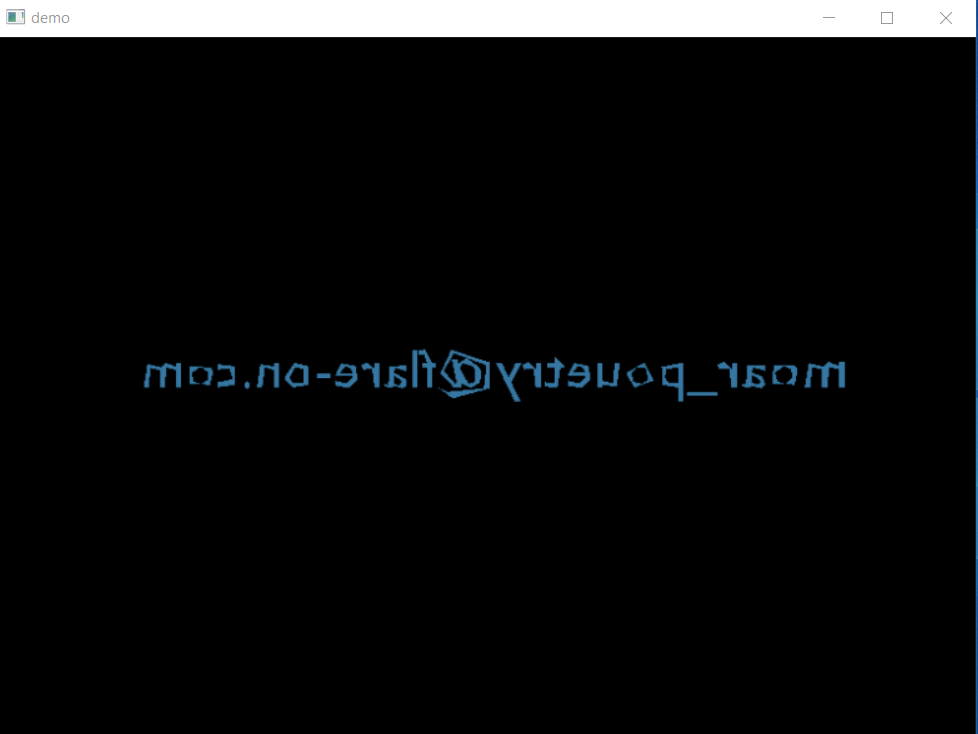

Continuing the execution draws the first frame of the animation before hitting the breakpoint again. The flag is displayed in the window, but it’s flipped.

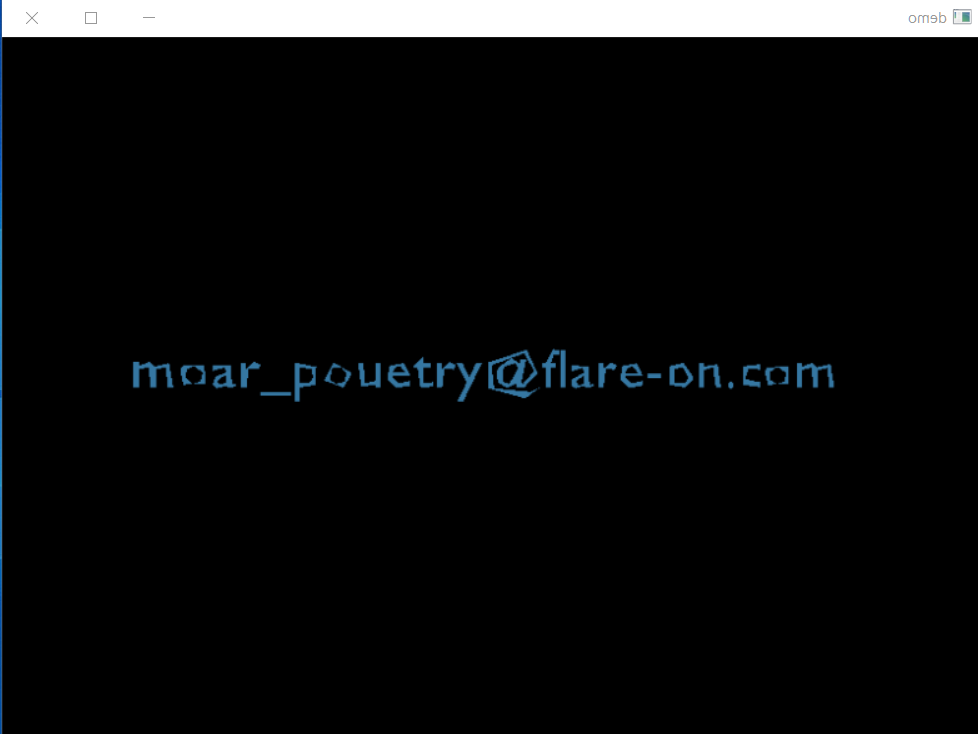

Flip it again and there it is:

moar_pouetry@flare-on.com

References

[1] https://www.usna.edu/Users/cs/roche/courses/s17si204/proj/3/files.php?f=gtkexample.c

[2] http://www.few.vu.nl/~eliens/pim/@archive/projects/jurgen/directx9.pdf