Basic Reverse Engineering (writeup) - Part 0x02

Introduction

I’ve started a course on Modern Binary Exploitation and throughout this course there are challenges and labs with which to practice exploitation techniques. It starts with an introduction to reverse engineering and I’ve decided to write about how I solved the challenges and take notes of the things I learned.

This (as you can see) is the third post and it will focus on the cmubomb challenge from the “Extended Reverse Engineering” class.

If you plan to take the course I highly encourage you not to read any further and try to solve the challenges yourself. You’ll learn much more that way.

For some of the challenges you don’t need to look at every assembly instruction but just looking at the function calls and byte/string comparisons you can immediately understand what input is expected without reversing the whole thing.

cmubomb

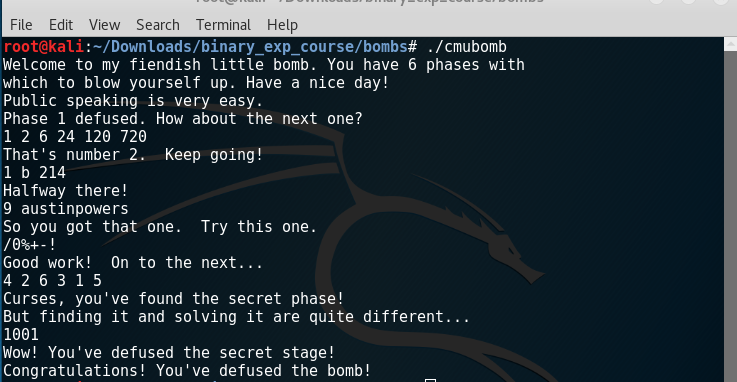

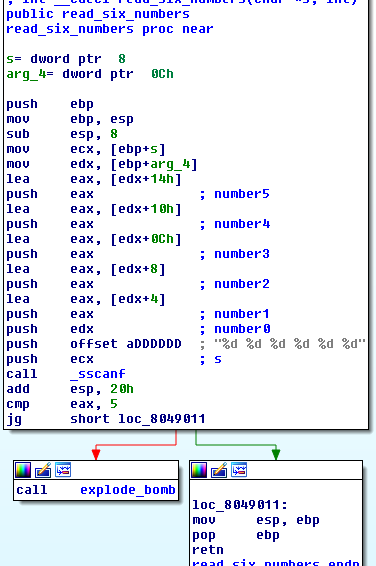

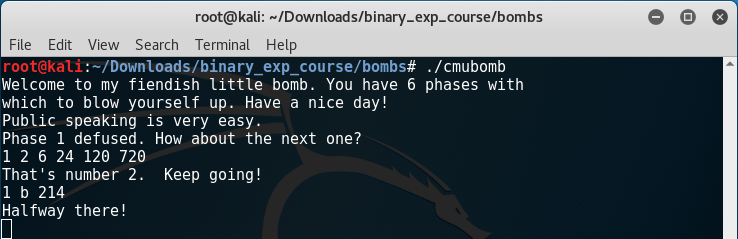

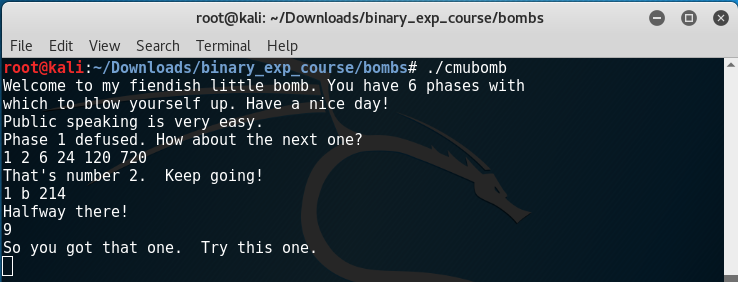

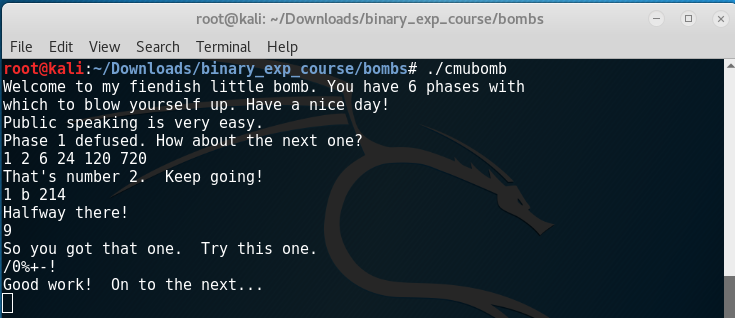

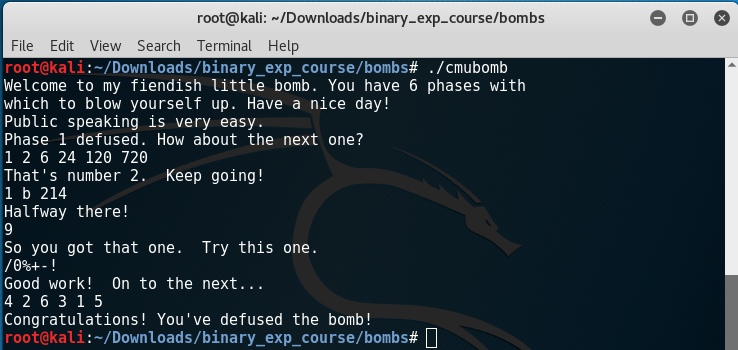

Starting the executable we’re presented with the following text:

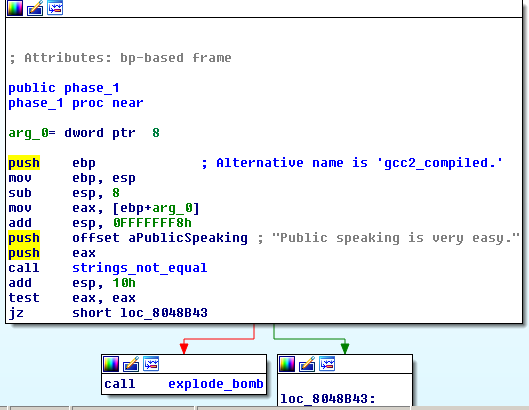

When we open the executable with IDA, there is a function called phase1. And when you open it in graph view the answer is obvious.

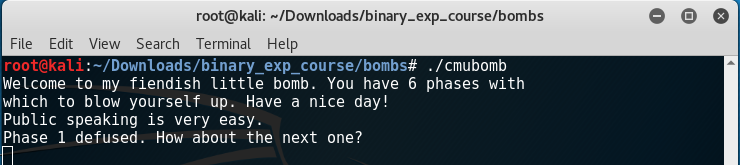

We enter ‘Public speaking is very easy.’ aaaaand…

Success!!

Phase 2

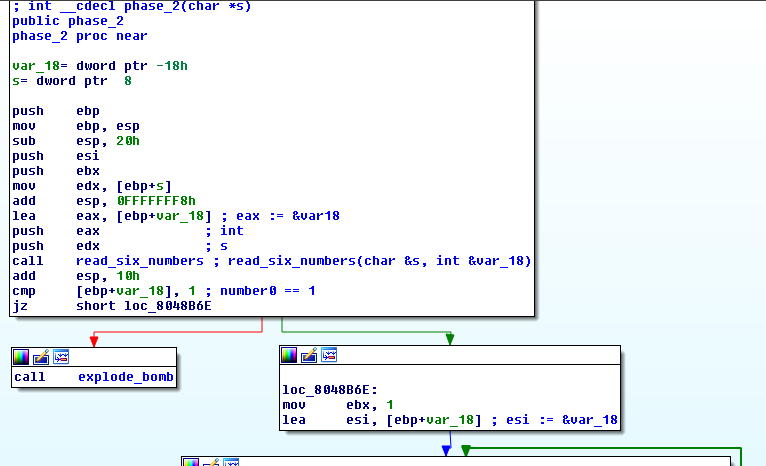

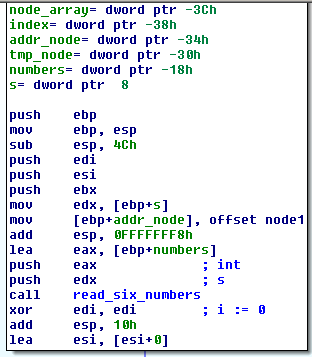

phase2:

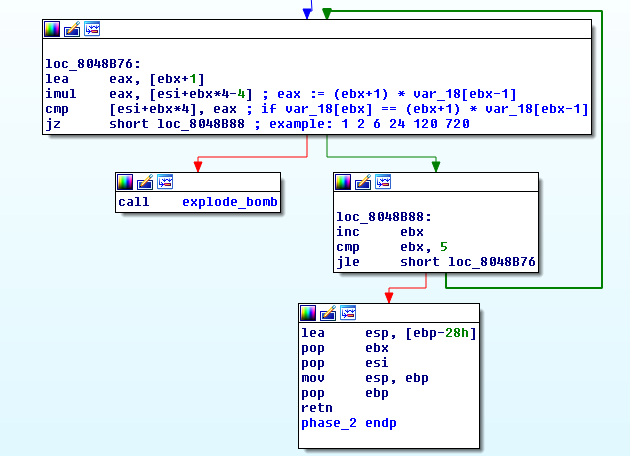

read_six_numbers:

As you can see phase2:

- reads 6 numbers

- stores them in the integer array

var_18 - expects that each number is

(i+1)times bigger than the previous

For example:

var_18[1] should be equal to 2 x var_18[0]

var_18[2] should be equal to 3 x var_18[1]

and so on.

I chose to try 1 2 6 24 120 720

Phase 3

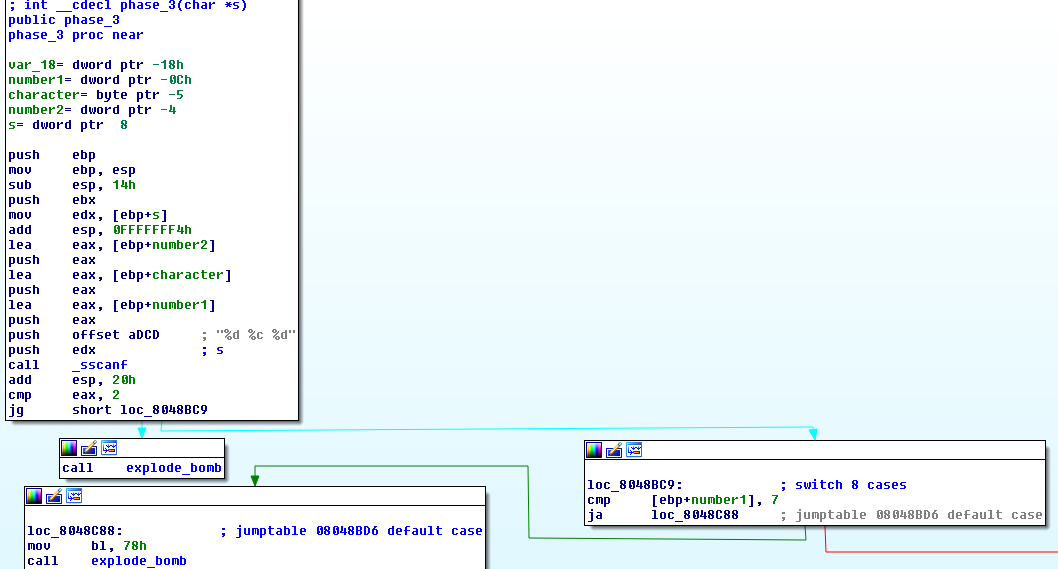

At phase 3 the expected input is a number, a character and again a number.

Next we enter a switch statement with 8 cases (0-7) and the first number of our input selects the case.

The case determines what character and second number should be expected form our input.

For case 1 that’s character 'b' and number2 = 214

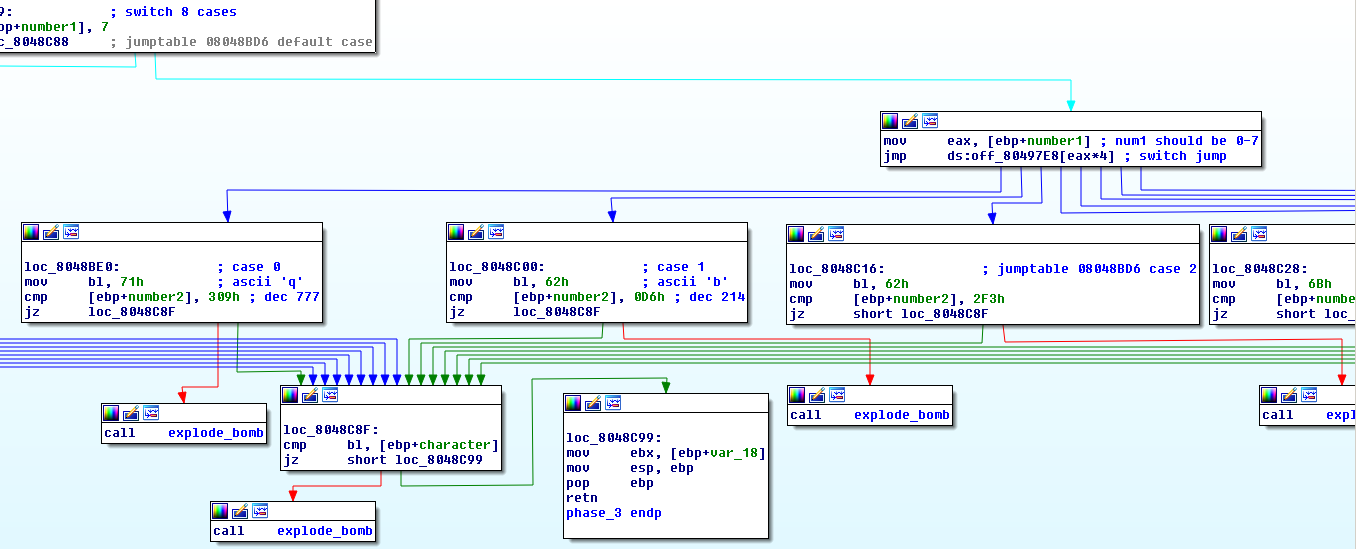

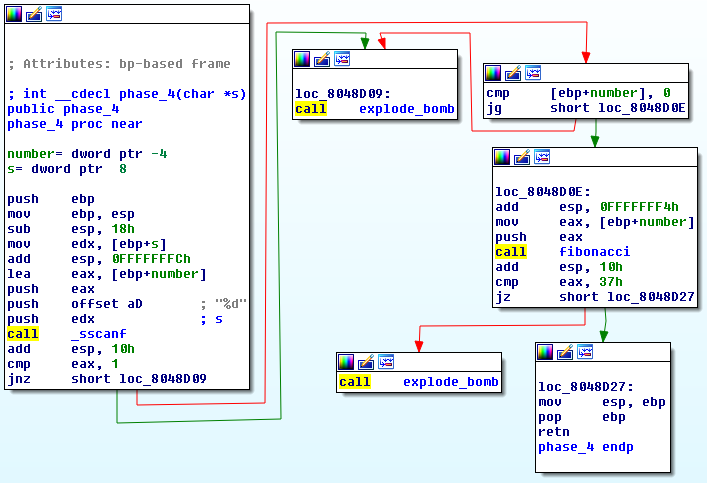

Phase 4

phase4:

Phase 4 accepts one number as input and passes that number as an argument to a function, that I renamed to 'fibonacci'. Then it compares the result that the function returns with 0x37 (55 in decimal).

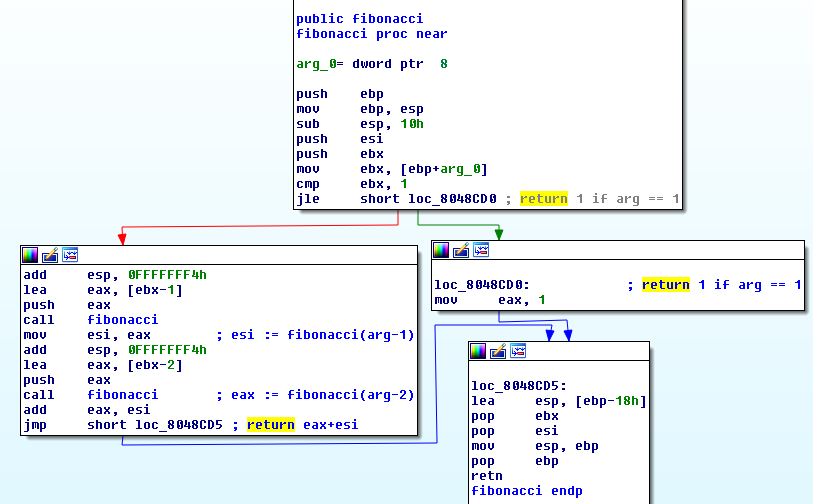

fibonacci:

As you can see the function calls itself, so it’s a recursive function. It returns 1 if the argument is <= 1.

If the argument is 2 it returns fibonacci(2-1) + fibonacci(2-2) which would return ``.

If the argument is 3 it returns fibonacci(3-1) + fibonacci(3-1) which is 2 + 1 = 3.

If the argument is 4 it returns fibonacci(4-1) + fibonacci(4-2) which is 3 + 2 = 5.

And so on.

I think you see why I renamed the function fibonacci. It returns the n-th fibonacci number.

So which input would produce a result of 55?

Phase 5

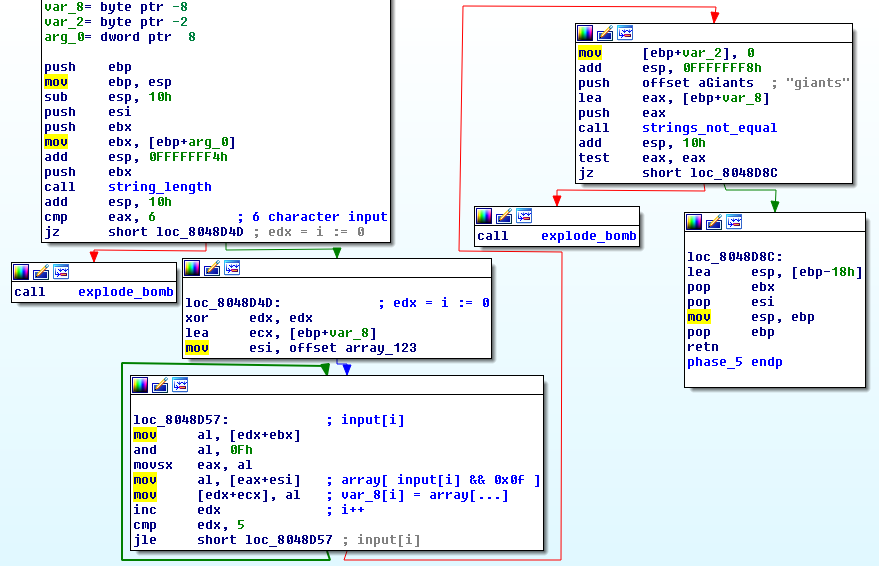

phase5:

- Our input is stored in

arg_0 - Accepts a 6 character input

- Uses

edxas an iteratori - Iterates through every element of our input ,

input[i] esipoints to the character arrayarray_123var_8is an empty array- The element at

position[ input[i] && 0x0f ]ofarray_123is stored in thei-thposition ofvar_8 var_8[i] = array_123[ input[i] && 0x0f ]- Finally compares

var_8with the string"giants"

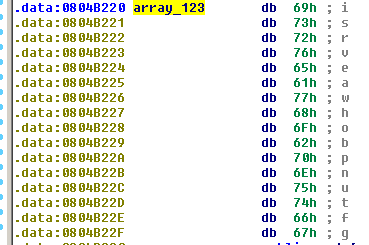

contents of array_123:

So we must enter such input, that it’s decoded by the algorithm to "giants". The AND operation, unlike XOR or NOT, is non inversible. That’s why we can’t just recreate the algorithm in reverse to see which string corresponds to "giants".

I wrote a bruteforce script that tries every 6 character combination of ascii printable characters.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

array_123 = 'isrveawhobpnutfg'

secret = 'giants'

output = []

for i in range(6):

# find the index of secret[i] character

# in array_123

index = array_123.find( secret[i] )

# try all ascii printable characters

# with which the algorithm returns the

# correct index

for byte in range(33,127):

if (byte & 0x0f) == index:

b = chr(byte)

output.append(b)

# use only the first found character

break

print(''.join(output))

$ ./phase5.py

/0%+-!

Phase 6

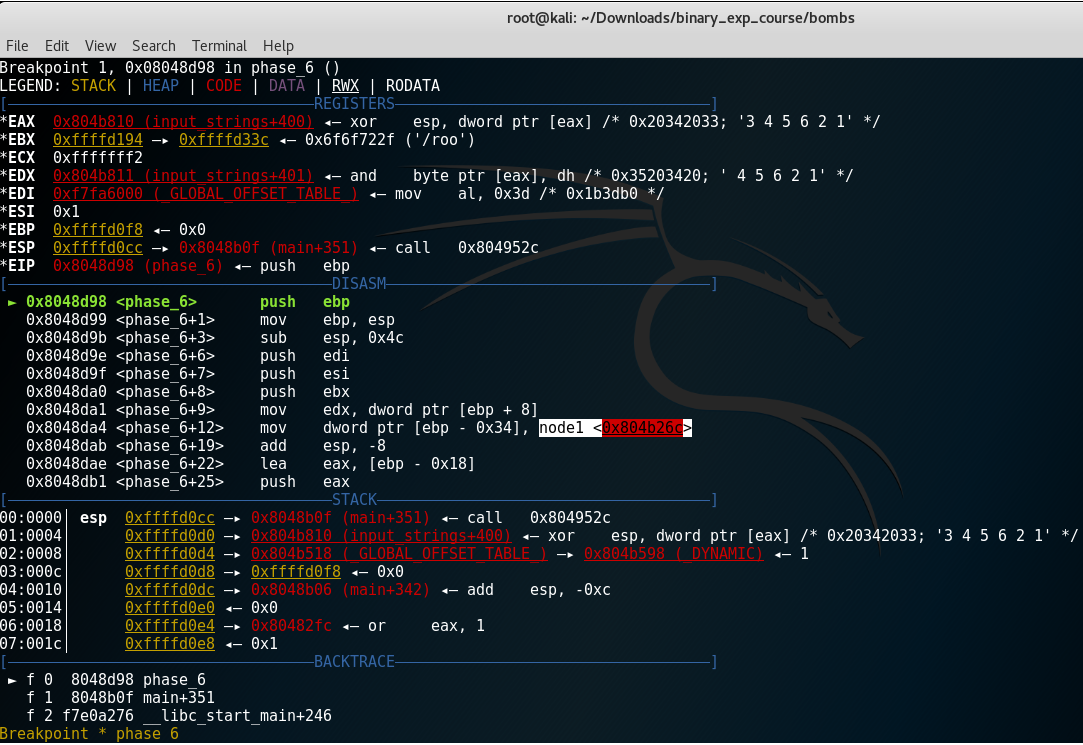

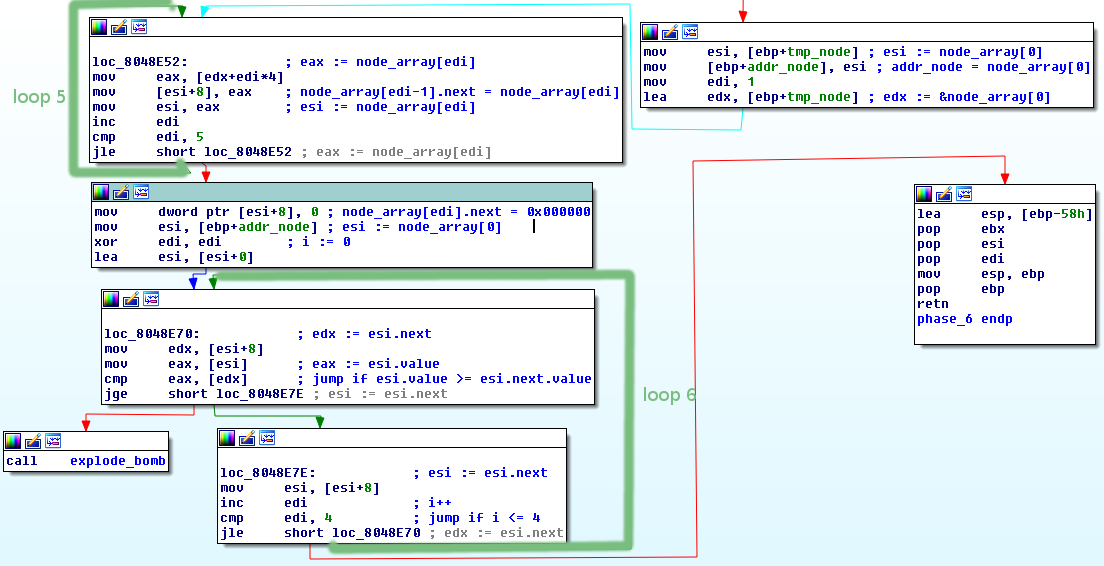

Phase 6 is harder then the previous phases. Let’s see the disassembly:

I’ve already renamed the variables and the arguments, but if you got this far it shouldn’t be a problem to find out their purpose yourself.

As you can see the function read_six_numbers is used again and then edi is prepared to be used as an loop iterator and initialized to zero. The numbers are save in the integer array numbers.

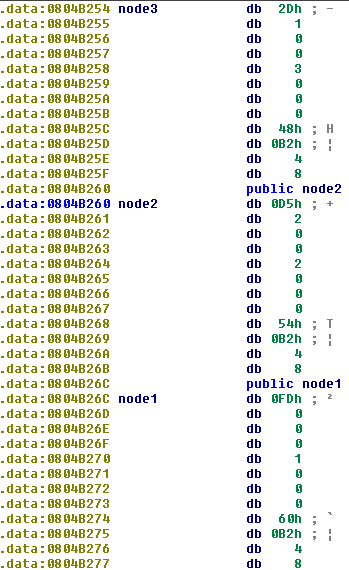

But before I continue, let’s see what is this mysterious node1.

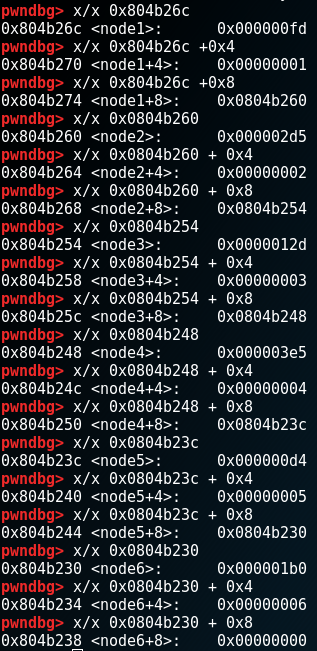

It looks like a structure. There are other nodes as well. Hmm.. Let’s check it in gdb (pwndbg).

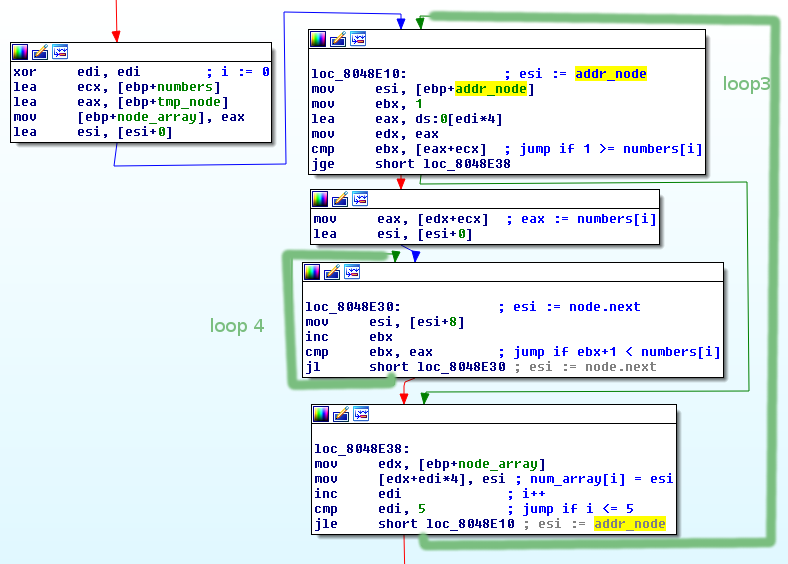

It’s a linked list of 6 structures. Node6 is the last one and points to null address. The structure looks something like this:

struct node{ // example address 0x804b26c

int value; // address 0x804b26c + 0x0

int id; // address 0x804b26c + 0x4

char* next_node; // address 0x804b26c + 0x8

}

OK, continuing with the disassembly…

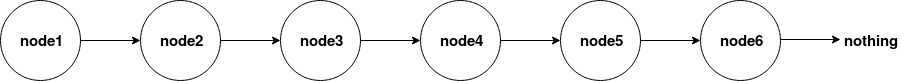

This part of the phase contains two loops.

- In the first (outer) loop each of our numbers is checked if it’s

<= 6(numbers[i] -1 <= 5) - The second (inner) loop checks if the current number is equal to another number in the array. If it is the bomb blows.

This means that the expected input is 6 unique numbers with values <= 6. That is 1,2,3,4,5,6 but in any order.

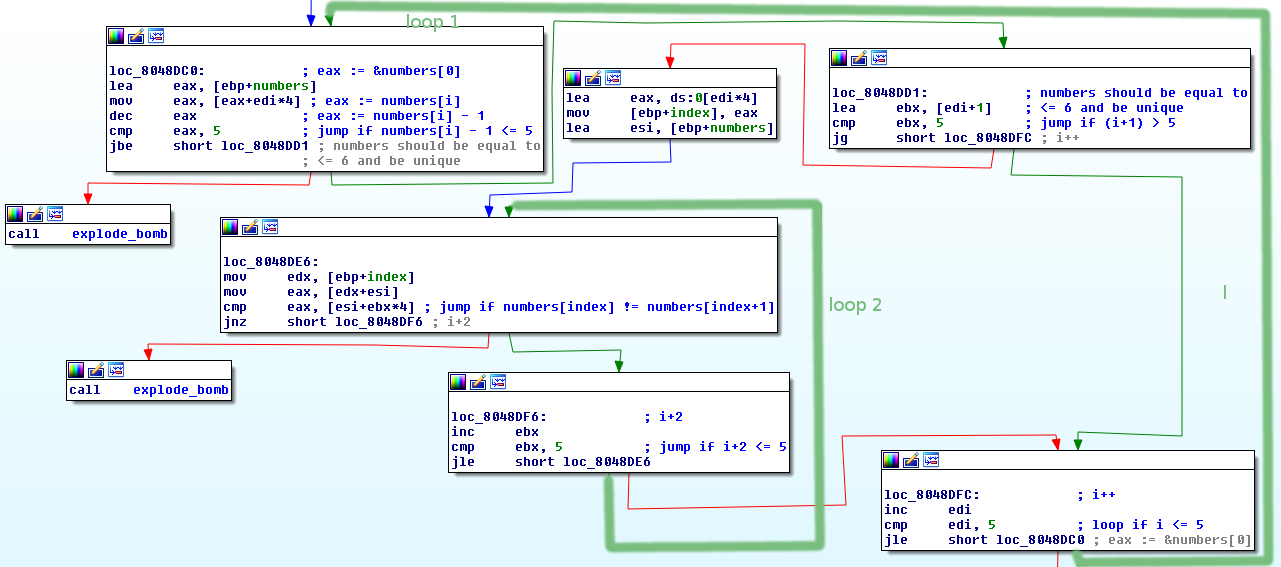

Again we have two loops.

- The outer loop (loop 3) iterates through our

numbers[i] - If

numbers[i]is<= 1, then skip the inner loop addr_nodewas pointing tonode1(the beginning of the linked list)-

The current node is added as the

i-thelement tonode_array[i] - If

numbers[i] > 1, then go to the inner loop (loop 4) - (

ebxstart with value of 1) Iterate untilebx+1 = numbers[i] - Set

esitonode.next - The result is that we get

numbers[i]-thnode of the list - The second loop completes and the

numbers[i]-thnode is added as thei-thelement ofnode_array[i]

So if our input is 2,1,4,3,6,5 node_array is going to be [node2, node1, node4, node3, node6, node5]

- The first loop iterates through

node_array - Sets the current node to point to the node thats next in the array

i=1;node_array[i-1].next = node_array[i]- After the loop last node is set to point to null address

If I use my previous example, the current linked list will be:

node2 -> node1 -> node4 -> node3 -> node6 -> node5 -> null

- The second loop goes through our new linked list

- Checks that the nodes are in such order, that their values are descending.

current_node.value >= current_node.next.value

And the script that bruteforces the solution:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import itertools

class node:

def __init__(self, address, value, number):

self.address = address

self.value = value

self.number = number

self.next_node = None

def set_next_node(self, next_node):

self.next_node = next_node

def phase6( numbers ):

node1 = node(0x0804b26c, 0x0fd, 0x1)

node2 = node(0x0804b260, 0x2d5, 0x2)

node3 = node(0x0804b254, 0x12d, 0x3)

node4 = node(0x0804b248, 0x3e5, 0x4)

node5 = node(0x0804b23c, 0x0d4, 0x5)

node6 = node(0x0804b230, 0x1b0, 0x6)

node_null = node(0x00000000, 0x0, 0x0)

node1.set_next_node( node2 )

node2.set_next_node( node3 )

node3.set_next_node( node4 )

node4.set_next_node( node5 )

node5.set_next_node( node6 )

node6.set_next_node( node_null )

node_array = []

# numbers must be unique

if len(numbers) != len( set(numbers) ):

print('BOOM! Not unique!')

return False

# numbers must be between 1 and 6

if max(numbers)-1 > 5:

print('BOOM! Bigger than 6!')

return False

# create node_array based on the input numbers

for i in range(6):

nd = node1

for j in range(1, numbers[i]):

nd = nd.next_node

node_array.append( nd )

# set connections for the nodes in the node_array

for i in range(1,6):

node_array[i-1].set_next_node( node_array[i] )

node_array[5].set_next_node( node_null )

# values of nodes in node_array should be in descending order

nd = node_array[0]

for i in range(6):

if nd.value < nd.next_node.value:

#print('Boom! Not ascending!')

return False

#print('Value of node %d: %x' % (nd.number, nd.value))

nd = nd.next_node

return True

for n in itertools.permutations('123456', 6):

numbers = []

for i in range( len(n) ):

numbers.append( int( n[i] ) )

if ( phase6( numbers ) ):

print('Valid key: ', numbers)

input()

# ./phase6.py

Valid key: [4, 2, 6, 3, 1, 5]

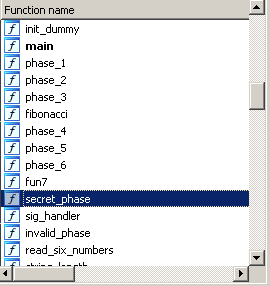

But wait! There’s more! If you look at list of function in IDA you’see that there is a secret phase:

Time to figure out how to access it.

THE SEARCH FOR THE SECRET PHASE

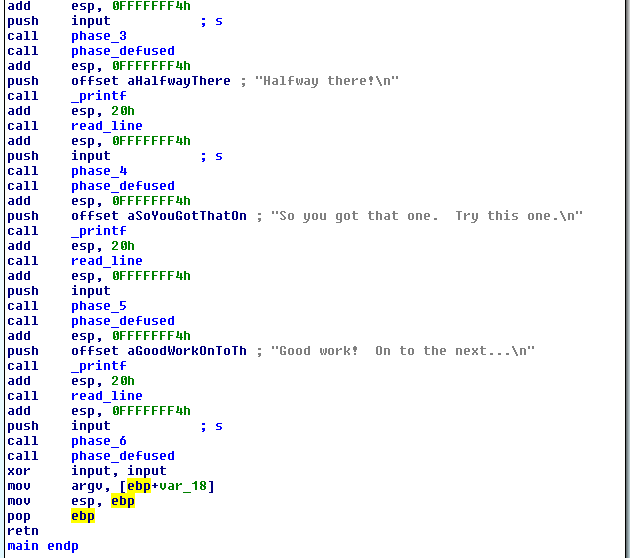

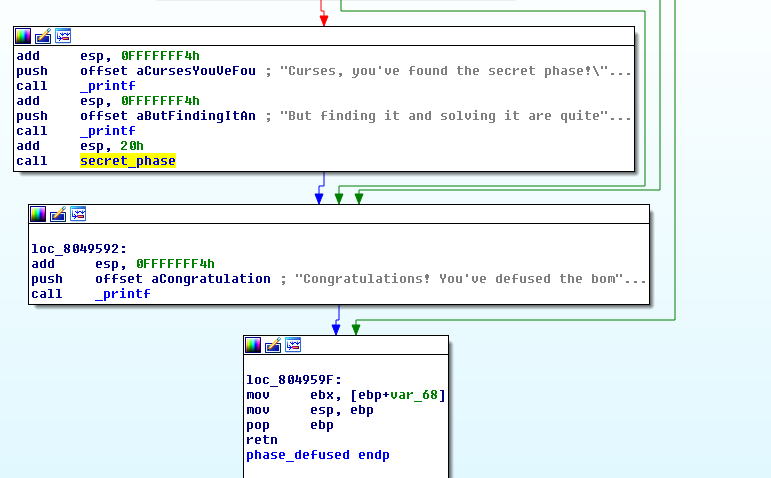

First, let’s check the cross references and see where that fucntion is called.

It gets called only from the function phase_defused. And phase_defused gets called in main.

And not only it’s called in main, but it’s called right after each phase! And now we should look into phase_defused.

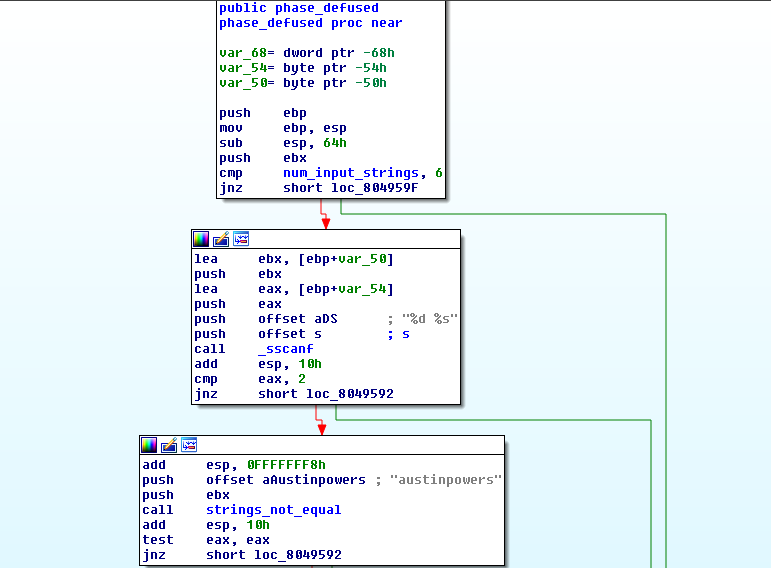

At the beginning it checks if num_input_strings == 6.

If it’s false then the function exits.

If it true, then it checks if the string s is in the form <integer> <string> as you can see from the sscanf call.

sscanf(s, "%d %s", &var_54, &var_50 )

If it’s not -> outputs the message that we’ve defused the bomb (the one after completing phase 6).

And if it is, it checks if var_50 is equal to "austinpowers". If true we enter the secret phase.

At first I thought that num_input_strings holds the number of strings in our current input. But then I started gdb (pwndbg) and noticed how the value changes.

pwndbg> run

Starting program: /root/Downloads/binary_exp_course/bombs/cmubomb

Welcome to my fiendish little bomb. You have 6 phases with

which to blow yourself up. Have a nice day!

Public speaking is very easy.

Breakpoint * phase_1

pwndbg> info br

Num Type Disp Enb Address What

1 breakpoint keep y 0x08048b20 <phase_1>

breakpoint already hit 1 time

2 breakpoint keep y 0x08048b48 <phase_2>

3 breakpoint keep y 0x08048b98 <phase_3>

4 breakpoint keep y 0x08048d98 <phase_6>

pwndbg> print num_input_strings

$2 = 1

pwndbg> conti

Continuing.

Phase 1 defused. How about the next one?

1 2 6 24 120 720

Breakpoint * phase_2

pwndbg> print num_input_strings

$3 = 2

pwndbg> conti

Continuing.

That's number 2. Keep going!

1 b 214

Breakpoint * phase_3

pwndbg> print num_input_strings

$4 = 3

pwndbg> conti

Continuing.

Halfway there!

9

So you got that one. Try this one.

/0%+-!

Good work! On to the next...

4 2 6 3 1 5

Breakpoint * phase_6

pwndbg> print num_input_strings

$5 = 6

num_input_strings, shows how many input strings have we typed, which is the same as telling us at which phase are we currently. It also makes sense that the string about bomb deactivation is printed after the check num_input_strings == 6.

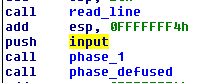

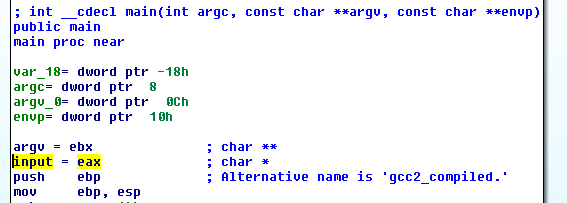

Now I wanted to see how our input is read and stored. In the main function you can see that 'input' points the input that is passed to phase_x functions. But 'input' as you can see below is just the eax register.

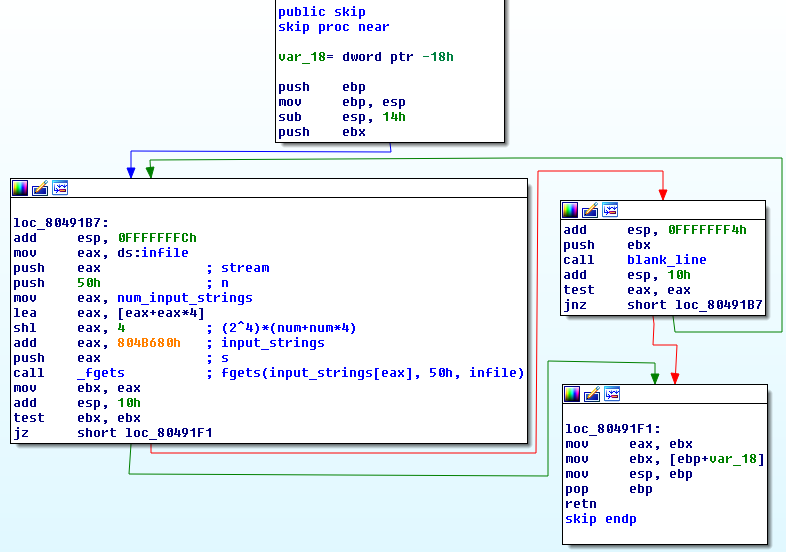

And what is the last thing that sets the eax register? The read_line function! At the beginning read_line calls skip function, I’ll show it first.

input_stringsis the buffer where all our input is stored.num_input_stringsis how many times we had to type an input (starting value is 0)input_stringsis split into 80 byte parts- every time we write an input it’s saved in a different part of input_strings

fgetsis used to read0x50(decimal 80) bytes and save them ininput_strings[eax]

num_input_strings = 0 (before phase_1) , 1 (before phase_2), 2 (before phase_3) ….

then

eax = (2^4) x (num_input_strings + num_input_strings x 4) will evaluate to = 0 , 80, 160, ….

then this is added to the address of input_strings which is equivalent to input_strings[eax] or input_strings[(2^4) x (num_input_strings + num_input_strings x 4)] or

input_strings[0]

input_strings[80]

input_strings[160]

….

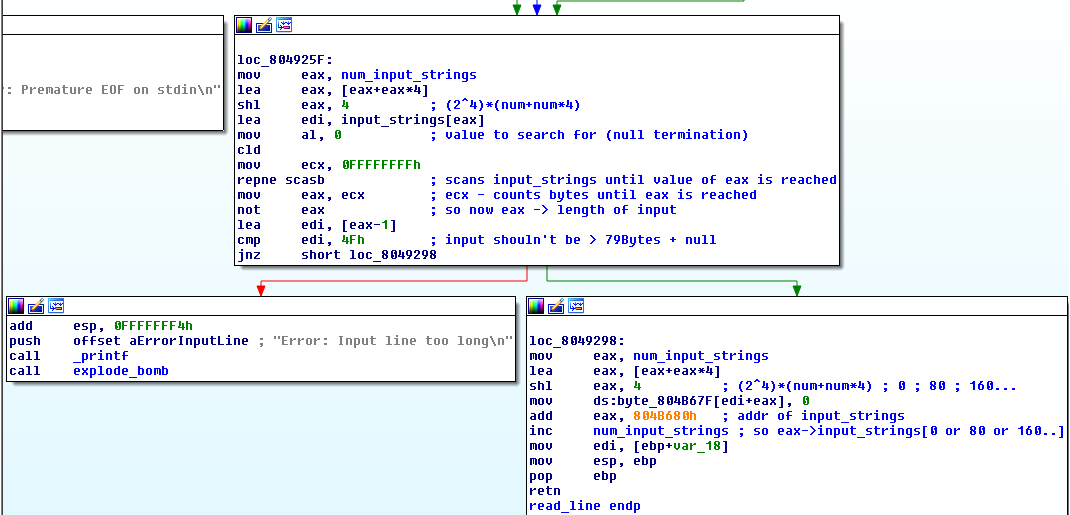

And now the read_line function (I’ll show only the end):

- Our input is checked if it is longer than 80 bytes

- eax is set to point to our input

num_input_stringsis incremented- the function returns

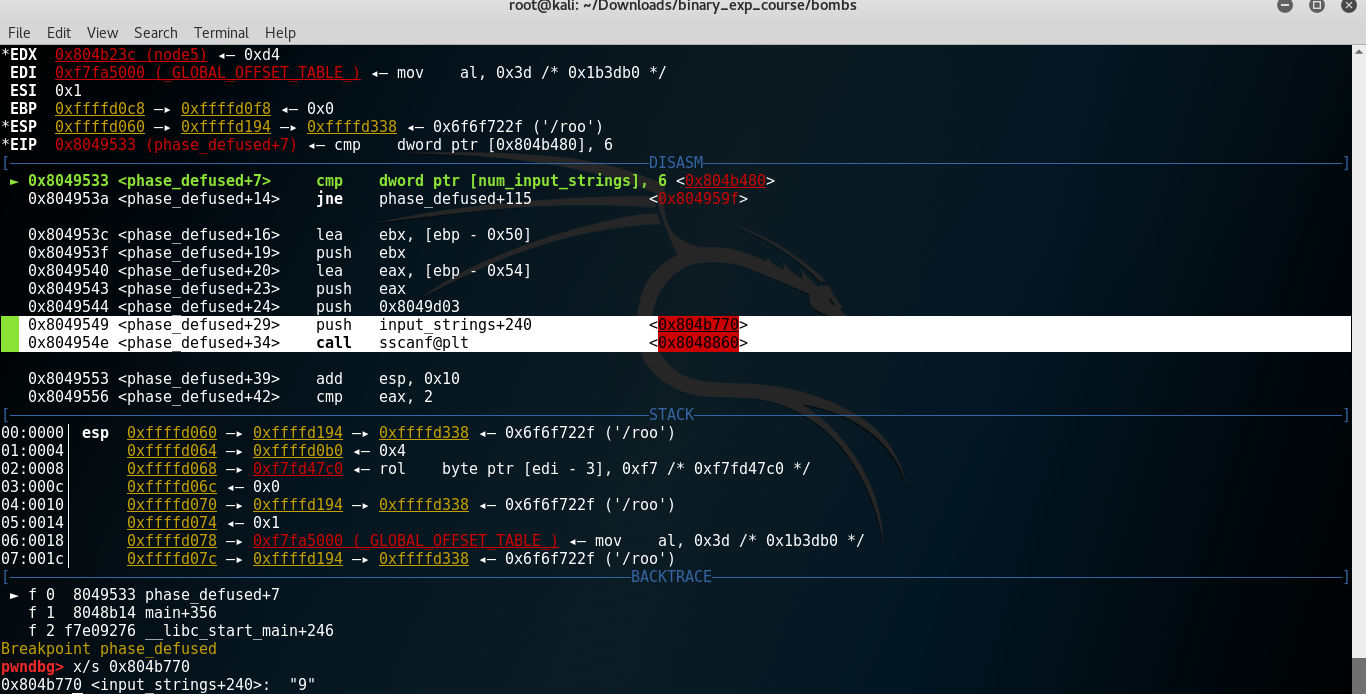

I need to see where in input_strings, phase_defused expects the input for the secret phase to be, because I tried and it doesn’t work with phase6 ("4 2 6 3 1 5 austinpowers"). I used gdb for that. I set a breakpoint at phase_defused and after the phase_6 stage.

You can see that sscanf expects the input buffer to be at input_strings with an offset of 240 bytes. And right now the string that is saved there is "9". This was the answer for phase 4. So at phase 4 we need to type "9 austinpowers"!

Although phase 4 accepts only one number as input, this works because sscanf reads only the first strings that match the format specifiers and ignores everything after that.

sscanf("1 2 this is a string", "%d %d", &num1, &num2);

// will save 1 and 2 at num1 and num2 respectively and ignore the rest "this is a string"

That means the buffer input_strings contains "9 austinpowers", but phase 4 reads only the "9" and after phase 6, phase_defused will read both.

sscanf("9 austinpowers", "%d %s", &var_54, &var_50 )

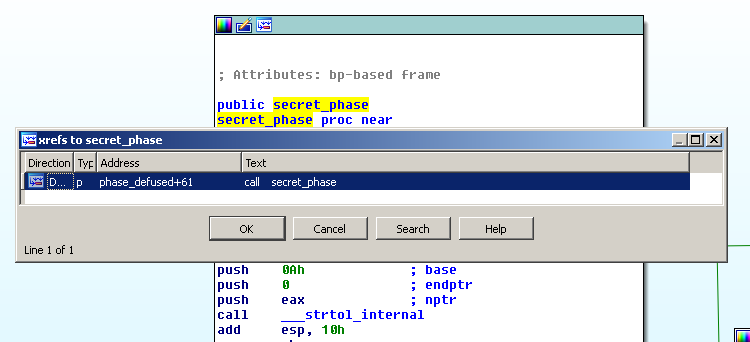

SECRET PHASE

- First calls

read_linefunction. - Then call

strtol(converts string to integer “9” -> 9) which means it accepts number as input. - The input should be

<= 1001 - Then calls the function

fun7(n1, num), where num is our number - The result from the function should be 7

Now let’s see what that n1 is.

It definitely looks like a structure again…

pwndbg> x/x 0x0804b320

0x804b320 <n1>: 0x00000024

pwndbg> x/x 0x0804b320 + 0x4

0x804b324 <n1+4>: 0x0804b314

pwndbg> x/x 0x0804b320 + 0x8

0x804b328 <n1+8>: 0x0804b308

pwndbg> x/x 0x0804b320 + 0xc

0x804b32c: 0x00000000

pwndbg> x/x 0x0804b314

0x804b314 <n21>: 0x00000008

pwndbg> x/x 0x0804b314 + 4

0x804b318 <n21+4>: 0x0804b2e4

pwndbg> x/x 0x0804b314 + 8

0x804b31c <n21+8>: 0x0804b2fc

pwndbg> x/x 0x0804b314 + 12

0x804b320 <n1>: 0x00000024

And again it looks like a linked list.

The structure looks like:

struct nn{ // example address 0x0804b320

int value; // 0x0804b320

char* next_left; //0x0804b320 + 0x4

char* next_right; //0x0804b320 + 0x8

}

I traced all nodes so here’s a visual representation of the list/graph:

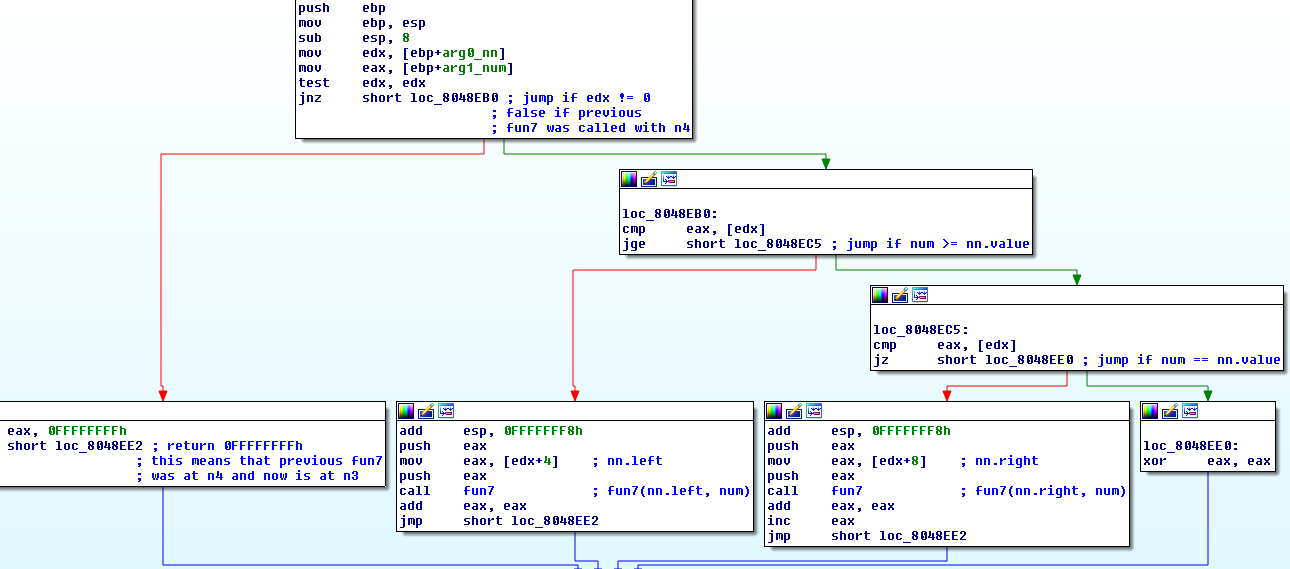

And the fun7 disassembly:

Below is pseudocode of what it does.

if arg0 == 0:

returns 0x0FFFFFFFF

if our number >= arg0.value:

if our number == arg0.value:

returns 0

result = fun7(arg0.right, our number) soo it's recursive

returns 2*result + 1

result = fun7(arg0.left, our number)

returns 2*result

The function calls itself until it reaches the end of the graph or our number == arg0.value. 4x nodes all have null next addresses and when fun7(arg0.left/right => 0x00000000 , number) is called => arg0 == 0 will be true.

To pass the secret phase we must find such an input that fun7 returns 7. There are two ways to find the right input.

- Bruteforce it

- Use logic

At first I solved it with bruteforce using this script:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

class nn:

def __init__(self,value):

self.value = value

self.next_left = None

self.next_right = None

n01 = nn(0x024)

n21 = nn(0x008)

n22 = nn(0x032)

n31 = nn(0x006)

n32 = nn(0x016)

n33 = nn(0x02d)

n34 = nn(0x06b)

n41 = nn(0x001)

n42 = nn(0x007)

n43 = nn(0x014)

n44 = nn(0x023)

n45 = nn(0x028)

n46 = nn(0x02f)

n47 = nn(0x063)

n48 = nn(0x3e9)

n01.next_left = n21

n01.next_right = n22

n21.next_left = n31

n21.next_right = n32

n22.next_left = n33

n22.next_right = n34

n31.next_left = n41

n31.next_right = n42

n32.next_left = n43

n32.next_right = n44

n33.next_left = n45

n33.next_right = n46

n34.next_left = n47

n34.next_right = n48

def fun7(n, num):

if n == None:

return 0x0FFFFFFFF

if num >= n.value:

if num == n.value:

return 0

result = fun7(n.next_right, num)

result = 2*result + 1

return result

result = fun7(n.next_left, num)

result = 2*result

return result

def secret_phase(num):

if num-1 > 0x3e8:

#print('Boom! Larger than %d' % (0x3e9))

return False

result = fun7(n01, num)

if result != 7:

#print('Boom! Not 7')

return False

return True

for i in range(0x3e9+1):

if secret_phase(i):

print('Key is: ', i)

input()

$ ./secret_phase.py

Key is: 1001

But you could solve it only by thinking a little and reverse the algorithm. Find the input by knowing the output (7).

- The end result of the first (outermost)

fun7shoud be7 - 7 is an odd number and the only way to get 7 is at

result = 2 x result + 1part of the code (I’ll call it the odd part, and2 x result-> the even part) - That means the result of the second

fun7should be3(2*3 +1 = 7) - To get 3 is only possible again at the odd part

- The result of the third

fun7should be1(2*1 +1 = 3 ) - Again, 1 can only be produced in the odd section

- The result of the fourth

fun7should be0(2*0 +2 = 1) - The only possible way fourth

fun7to return0is our number to be equal to some of the values of the n4x nodes. - Also note that all return values (except 0) are odd

Below are the values of all nodes:

n01 = 0x024

n21 = 0x008

n22 = 0x032

n31 = 0x006

n32 = 0x016

n33 = 0x02d

n34 = 0x06b

n41 = 0x001

n42 = 0x007

n43 = 0x014

n44 = 0x023

n45 = 0x028

n46 = 0x02f

n47 = 0x063

n48 = 0x3e9

Let’s start again at the first (outermost) fun7 -> fun7(n1, our_num):

- Could our num be equal to

n41 = 0x001? No, becausen01 (0x24) > n41and we’ll end up at the even section of the code and couldn’t get an odd number. - That means every

n4xnode with value less than0x24(n41, n42, n43, n44) is no good - What about

n45 = 0x028? No, becase the secondfun7will be called with argumentn22=0x32and everything less will get us to the even section. - So

n45andn46are not good. n47 = 0x063? No, because the thirdfun7will have an argumentn34 = 0x06bandn47 < n34- The only answer left is

0x3e9(1001 in decimal)