Crypto - Part 1. Breaking XOR Encryption.

Introduction

In the Crypto series of posts I’ll try to explain different encryption algorithms, implement them in code and then try to break them. They’re also writeups for the cryptopals crypto challenges and I recommend trying to solve them youtself before reading this and other crypto posts.

I’m not a cryptographer, nor am I an expert in programming! The purpose of these posts (and the blog in general) is for me to write down what I’ve learned so it can be useful to others (and for others to point out my mistakes!).

Single-byte XOR cipher

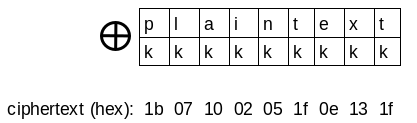

This cipher applies the XOR operation on every byte of the plaintext with the same one-byte key. For example:

key = 'k'

plaintext = 'plaintext'

ciphertext = kkkkkkkkk XOR plaintext

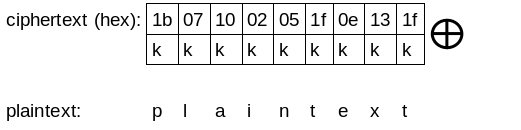

And to decrypt the message, XOR every byte of the ciphertext with the key:

key = 'k'

plaintext = kkkkkkkkk XOR ciphertext

Below is a function that does XOR of two strings of equal length:

def xor(str1, str2):

if len(str1) != len(str2):

raise "XOR EXCEPTION: Strings are not of equal length!"

s1 = bytearray(str1)

s2 = bytearray(str2)

result = bytearray()

for i in range( len(s1) ):

result.append( s1[i] ^ s2[i] )

return str( result )

The function for encryption and decryption:

def single_byte_xor(plaintext, key):

if len(key) != 1:

raise "KEY LENGTH EXCEPTION: In single_byte_xor key must be 1 byte long!"

return xor(plaintext, key*len(plaintext))

Break the single-byte XOR cipher

This cipher is essentialy a substitution cipher, so it’s vulnerable to frequency analysis and because the key is only one byte it’s also easy to bruteforce (there are only 256 possible keys…).

The frequency analysis is suitable for longer messages, so I’ll implement only the bruteforce method which always works regardless of the message length.

But when we try every one of the 256 possible keys, how do we know that the produced output is the actual plaintext? If the plaintext is written in english, we need a way to test if a given string is an english text.

To decide wether a string is an english text I’ll use some the following rules:

- The string contains only ascii printable characters

- Letter ‘E’ and space are the most frequent characters (for sufficiently long messages)

- The letters E,T,A,O,I,N make up around 40% of the text (those are the most frequent letters in the english language)

- The digraphs cj, fq, gx, hx, jf, jq, jx, jz, qb, qc, qj, qk, qx, qz, sx, vf, vj, vq, vx, wx, xj, zx never occur in english words

- Punctuation makes up to 2%-3% of the text (for short messages up to 10%).

- Has at least one vowel (every word should have at least one vowel)

- Around 80%-90% or more of the text should be made up of letters

I found the digraphs using the following script and this dictionary which contains 355k english words.

import string, itertools

f = open('words.txt','r')

file = f.read().lower()

f.close()

digraphs = []

for digraph in itertools.product(string.lowercase, repeat=2):

d = ''.join(digraph)

if file.count(d) == 0:

digraphs.append(d)

print "Digraphs: ", digraphs

For the punctuation statistic similar script was used and a 1000 page ebook.

import string

f = open('book.txt','r')

file = f.read().lower()

f.close()

cnt = 0

for char in string.punctuation:

cnt += file.count(char)

print "Punctuation makes up %f %% of the text!" % ( float(cnt)*100/len(file) )

And below is the code I wrote that checks if a given string is an english text, by using the rules mentioned above. It’s not perfect but most of the time works well enough.

import string

def has_nonprintable_characters( text ):

for char in text:

if char not in string.printable:

return True

return False

def has_vowels( text ):

vowels = list("eyuioa")

for char in vowels:

if char in text:

return True

return False

def has_forbidden_digraphs( text ):

forbidden_digraphs = ['cj','fq','gx','hx','jf','jq','jx','jz','qb','qc','qj','qk','qx','qz','sx','vf','vj','vq','vx','wx','xj','zx']

for digraph in forbidden_digraphs:

if digraph in text:

return True

return False

def has_necessary_percentage_frequent_characters( text, p=38 ):

most_frequent_characters = list("etaoin")

cnt = 0

for char in most_frequent_characters:

cnt += text.count(char)

percent_characters = float(cnt)*100/len(text)

# The most_frequent_characters shoud be more than 38% of the text.

# For short messages this value may need to be lowered.

if (percent_characters < p):

return False

return True

def has_necessary_percentage_punctuation( text, p=10 ):

cnt = 0

for char in string.punctuation:

cnt += text.count(char)

# Punctuation characters should be no more than 10% of the text.

punctuation = float(cnt)*100/len(text)

if punctuation > 10:

return False

return True

def has_english_words( text ):

most_frequent_words = ['the', 'and', 'have', 'that', 'for',

'you', 'with', 'say', 'this', 'they', 'but', 'his', 'from',

'that', 'not', "n't", 'she', 'what', 'their', 'can', 'who',

'get', 'would', 'her', 'make', 'about', 'know', 'will',

'one', 'time', 'there', 'year', 'think', 'when', 'which',

'them', 'some', 'people', 'take', 'out', 'into','just', 'see',

'him', 'your', 'come', 'could', 'now', 'than', 'like', 'other',

'how', 'then', 'its', 'out', 'two', 'more ,these', 'want',

'way', 'look', 'first', 'also', 'new', 'because', 'day',

'more', 'use', 'man', 'find', 'here', 'thing', 'give', 'many']

for word in most_frequent_words:

if word in text:

return True

return False

def is_english( input_text ):

text = input_text.lower()

if has_nonprintable_characters( text ):

return False

# If the text contains one of the most frequent english words

# it is very likely that it's an english text

if has_english_words( text ):

return True

if not has_vowels( text ):

return False

if has_forbidden_digraphs( text ):

return False

if not has_necessary_percentage_frequent_characters( text ):

return False

if not has_necessary_percentage_punctuation( text ):

return False

return True

Now we are ready to construct the bruteforce function.

def break_single_byte_xor( ciphertext ):

keys = []

plaintext = []

for key in range(256):

text = single_byte_xor( ciphertext , chr(key))

if is_english( text ):

keys.append( chr(key) )

plaintext.append( text )

# There might be more than one string that match the rules of the is_english function.

# Return all those strings and their corresponding keys and inspect visually to

# determine which is the correct plaintext.

return keys, plaintext

Lets test it!

msg = 'This is a very secret message!'

key = '\x0f'

ciphertext = single_byte_xor(msg, key)

k, pt = break_single_byte_xor( ciphertext )

print "Keys: ", k

print "Plaintexts: ", pt

The output is:

Keys: ['\x0f']

Plaintexts: ['This is a very secret message!']

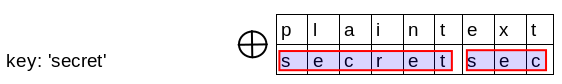

Repeating-key XOR cipher

This cipher uses a key that is more than one byte long. The key is repeated until it matches the length of the message.

For example:

key='secret'

plaintext = 'plaintext'

ciphertext = secretsec XOR plaintext

Here is the implementation:

def repeating_key_xor(plaintext, key):

if len(key) == 0 or len(key) > len(plaintext):

raise "KEY LENGTH EXCEPTION!"

ciphertext_bytes = bytearray()

plaintext_bytes = bytearray(plaintext)

key_bytes = bytearray(key)

# XOR every byte of the plaintext with the corresponding byte from the key

for i in range( len(plaintext) ):

k = key_bytes[i % len(key)]

c = plaintext_bytes[i] ^ k

ciphertext_bytes.append(c)

return str(ciphertext_bytes)

Breaking the repeating-key XOR cipher

This one is trickier. There are mainly two steps here:

- Find the key size

- Crack the key

Finding the key size is done by the following algorithm:

- Make a guess about the key length

- Divide the ciphertext by blocks, each with length equal to the one chosen at step 1

- Calculate the hamming distance between the first few blocks (I had best results with 4-5 blocks) and then take the average

- Normalize the hamming distance by dividing it by the chosen key length

- The key length that gives the smallest normalized hamming distance is PROBABLY the actual key length (if it’s not, it is usually one of the three with the smallest normalized hamming distance)

Hamming distance is equal to the number of bits by which two strings of equal length differ. Take this two bytes:

00101010

01000010

The hamming distance between them is 3, because they differ by three bits - the 4th, the 6th and the 7th (counting from the least significant).

Calculating the hamming distance is easy - just XOR the two strings/bytes and count the number of ones in the resuting string.

def hamming_distance(str1, str2):

result = xor(str1, str2)

return bin( int( result.encode('hex'), 16) ).count('1')

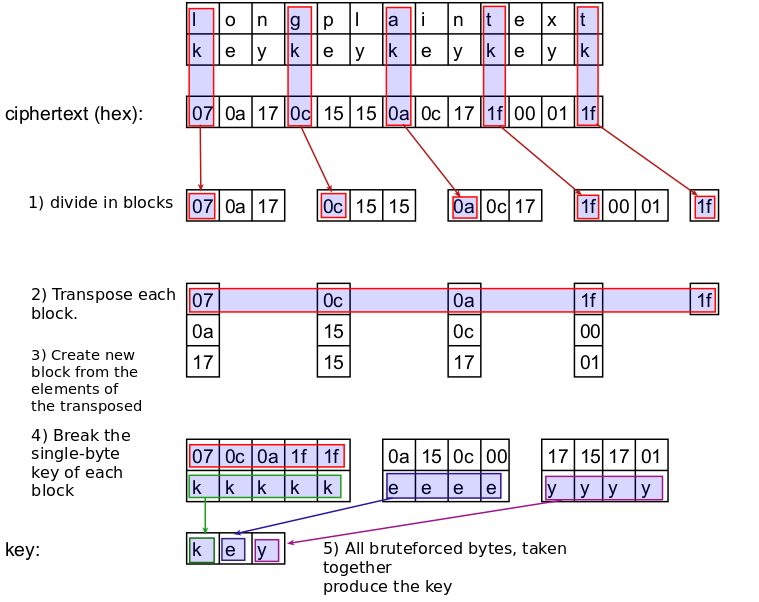

To crack the key there are several steps:

- Divide the ciphertext by blocks with equal length, same as the length of the key

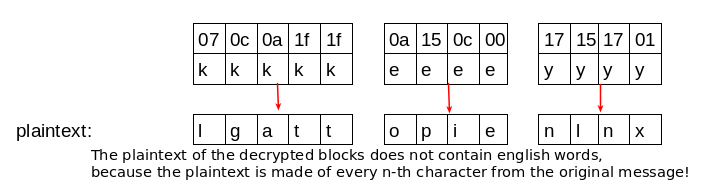

- Transpose the blocks. That is, make a new block from the first bytes of the blocks, then a second block containing the second bytes of the blocks and so on…

- Each of the transposed blocks contains bytes that are encrypted with the same byte. That is the single-byte XOR cipher! And we already know how to break it.

- Crack the single-byte key for each of the transposed blocks.

- All bytes taken together produce the key

Lets illustrate those steps:

By now I hope you see how this method works :)

Here is the function I wrote for finding the probable key length:

def find_xor_keysize( ciphertext, hamming_blocks, minsize=2, maxsize=10 ):

hamming_dict = {} # <keysize> : <hamming distance>

if (hamming_blocks*maxsize) > len(ciphertext):

raise "OUT OF BOUND EXCEPTION! Lower the hamming_blocks or the key maxsize!"

for key_length in range(minsize, maxsize):

# Take the first 'hamming_blocks' blocks

# with size key_length bytes

blocks = []

for i in range(hamming_blocks):

blocks.append( ciphertext[i*key_length : (i+1)*key_length] )

# Calculate the hamming distance between the blocks

# (first,second) ; (first,third) ; (first,fourth)

# (second, third) ; (second, fourth)

# (third, fourth) ; There are sum(1,hamming_blocks-1) combinations

hd = [] # hamming distance

for i in range( hamming_blocks - 1 ):

for j in range( i+1, hamming_blocks ):

hd.append( hamming_distance(blocks[i], blocks[j] ))

hd_average = float(sum(hd))/len(hd)

hd_normalized = hd_average/key_length

hamming_dict[key_length] = hd_normalized

# Get sorted (ascending order) list of tuples. Sorted by dictionary value (i.e. hamming distance)

sorted_list_tuples = sorted(hamming_dict.items(), key=lambda x: x[1])

# One of the three keys that produced the lowest hamming distance

# is likely the actual size

return [ sorted_list_tuples[0][0], sorted_list_tuples[1][0], sorted_list_tuples[2][0] ]

The cracking step turns out to be a little harder. The transposed blocks are every n-th character of the ciphertext and so their corresponding plaintext isn’t composed of english words. This makes it harder to distinguish which one-byte key produces the correct plaintext. That’s why it’s necessary to have a long message (longer message -> longer blocks) to be able to use statistical methods on the transposed blocks.

1) I take every possible one-byte key for a single block and test if it produces ascii printable output. If it does, I store it in a list (that way I filter out may invalid keys). There is one such list for every block, which contains the keys that produce printable output.

block1: keys[a,b,c,d]

block2: keys[1,2,3]

block3: keys[w,x,y,z]

2) Then I store all those lists in another list. This list now contains all possible one-byte keys for every block.

list: [ [a,b,c,d], [1,2,3], [w,x,y,z] ]

3) After that I generate all possible combinations of the collected single-byte keys (with key length as returned from find_xor_keysize) using that list.

a1w

a1x

a1y

a1z

a2w

a2x

and so on…

4) Try every one of the produced multi-byte keys against the whole ciphertext, and test if the output is an english text.

ciphertext

xor

a1wa1wa1wa

=

output

test if output is english text

import itertools

def divide_text_by_blocks(text, block_size):

blocks = []

num_blocks = len(text)/block_size

for i in range(num_blocks):

blocks.append( text[i*block_size : (i+1)*block_size] )

return blocks

def transpose( blocks ):

transposed = []

block_size = len(blocks[0])

num_blocks = len(blocks)

for i in range(block_size):

tmp = []

for j in range(num_blocks):

# tmp is composed of the i-th character of every block

tmp.append( blocks[j][i] )

transposed.append( ''.join(tmp) )

return transposed

def has_necessary_percentage_letters( text,p=80 ):

characters = string.letters + ' '

cnt = 0

for char in characters:

cnt += text.count(char)

percent_characters = float(cnt)*100/len(text)

# The characters shoud be more than 38% of the text.

if (percent_characters < p):

return False

return True

def is_printable_text( text ):

text = text.lower()

if has_nonprintable_characters(text):

return False

if not has_necessary_percentage_punctuation( text ):

return False

if not has_necessary_percentage_letters( text ):

return False

if not has_vowels( text ):

return False

return True

def break_repeat_key_xor( ciphertext ):

# Tweaking this is useful. Lower value (0.03-0.05) helps find longer keys

# Higher value (0.1 - 0.15) helps find shorter keys

hamming_blocks = int(len(ciphertext)*0.06)

key_sizes = find_xor_keysize(ciphertext, hamming_blocks , 2)

print "Key sizes: ", key_sizes

for ks in key_sizes:

print "Current key size: ", ks

blocks = divide_text_by_blocks(ciphertext, ks)

transposed = transpose(blocks)

all_keys = [] # list of lists. One list for every block. The list has all possible one-byte keys for the block.

for block in transposed:

block_keys = [] # store all possible one-byte keys for a single block

for key in range(256):

text = single_byte_xor( block , chr(key))

if is_printable_text(text):

block_keys.append(chr(key))

print block_keys

all_keys.append(block_keys)

real_keys = [] # Stores keys with size ks. Generated from all possible combinations of one-byte keys contained in all_keys

for key in itertools.product(*all_keys):

real_keys.append( ''.join(key) )

print "Keys to try: ", len(real_keys)

# Try every possible multy-byte key.

for key in real_keys:

text = repeating_key_xor(ciphertext,key)

if is_english(text):

print "Plaintext: " ,text

print "Key: ", key

raw_input()

print "=================="

Lets test it!

msg = '''In today's electronic communication forums, encryption can be very

mportant! Do you know for a fact that when you send a message to someone else,

that someone hasn't read it along the way? Have you ever really sent something

you didn't want anyone reading except the person you sent it to? As more and

more things become online, and "paperless" communication predictions start

coming true, it's all the more reason for encryption. Unlike the normal U.S.

Mail where it is a crime to tamper with your mail, email-reading can commonly

go unnoticed on electronic pathways as your message hops from system to system

on its route towards its final destination. Just think, the average Internet

letter makes at least two hops before it reaches its recipient, usually more.

Even on public BBS's, your mail is usually stored in plaintext. '''

key = "r!ck_@nd_m0rty"

c = repeating_key_xor(msg, key)

break_repeat_key_xor2(c)

And the output is:

Key sizes: [14, 7, 2]

Current key size: 14

['r']

['!']

['c']

['k']

['_']

['@']

['n']

['d']

['_']

['m']

['0', '7']

['r']

['t']

['y']

Keys to try: 2

Plaintext: In today's electronic communication forums, encryption can be very

mportant! Do you know for a fact that when you send a message to someone else,

that someone hasn't read it along the way? Have you ever really sent something

you didn't want anyone reading except the person you sent it to? As more and

more things become online, and "paperless" communication predictions start

coming true, it's all the more reason for encryption. Unlike the normal U.S.

Mail where it is a crime to tamper with your mail, email-reading can commonly

go unnoticed on electronic pathways as your message hops from system to system

on its route towards its final destination. Just think, the average Internet

letter makes at least two hops before it reaches its recipient, usually more.

Even on public BBS's, your mail is usually stored in plaintext.

Key: r!ck_@nd_m0rty

==================

mportant! Do'you know for f fact that whbn you send a jessage to sombone else,

thas someone hasn t read it aloig the way? Hfve you ever rbally sent sombthing

more things bbcome online, fnd "paperless% communicatioi predictions ttartand

coming tuue, it's all she more reasoi for encryptihn. Unlike thb normal U.S.

Jail where it ns a crime to samper with yorr mail, email*reading can chmmonly

go unnhticed on elecsronic pathwayt as your messfge hops from tystem to systbm

on its routb towards its ainal destinatnon. Just thiik, the averagb Internet

letser makes at lbast two hops eefore it reacoes its recipibnt, usually mhre.

Even on prblic BBS's, yhur mail is usrally stored ii plaintext.

Key: r!ck_@nd_m7rty

==================

Current key size: 7

[]

[]

[]

[]

[]

[]

[]

Keys to try: 0

Current key size: 2

[]

[]

Keys to try: 0

And it worked! There were two possible keys for one of the blocks - ['0', '7']. If the message was shorter there would’ve beem

many possible keys with thousands of combinations (or none).

msg = '''In today's electronic communication forums, encryption can be very

mportant! Do you know for a fact that when you send a message to someone else,

that someone hasn't read it along the way? '''

And the output is:

Key sizes: [14, 4, 7]

Current key size: 14

['r']

['\x0c', '\r', '!', '#', '%', "'", ',', '-', '6', '7']

['c']

['k', '|', '}']

['B', 'Q', 'R', 'S', 'X', 'Y', '[', ']', '^', '_', 'b', 'c', 'q', 'r', 's', 'x',

'y', '{', '}', '~', '\x7f']

[]

['n']

['d']

['I', 'J', 'X', 'Z', ']', '_']

['F', 'G', 'm', 'u']

['0']

['^', 'e', 'r']

['t']

['N', 'O', 'X', 'Y', '[', ']', '^', '_', 'n', 'o', 'x', 'y', '{', '}', '~']

Keys to try: 0

Current key size: 4

[]

[]

[]

[]

Keys to try: 0

Current key size: 7

[]

[]

[]

[]

['X', 'Y', '[', '^', '_', 'r']

[]

['n']

Keys to try: 0

As you can see, for some blocks there are many possible keys, and for others none were found.